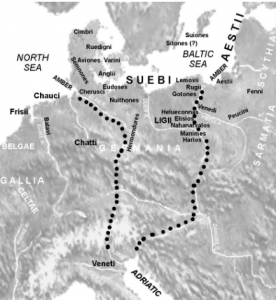

Kyseessä olisivat muinaiset veneetit. Näin väittää kanadanvirolainen Anders Pääbo, joka on tutkinut ennen ajanlaskun alkua Adrianmeren rannalla ja myös Baltian rannikolla asuneiden tuon nimisten kansojen perintönä jääneitä roomalaisia tekstejä ja paikannimistöä ja lainosanoja molemmilla alueilla.

Italian kansat rautakaudella. Huom! Latinalaisten aika vaatimaton siivu faliskien ja umbri(alaist)en välissä. Lisäksi Rooma ei tuolloin kuulunut heidän ydinalueeseensa, vaan se oli (ensimmäinen?) heidän perustamansa colonia pohjoisesta etelään joh- tavien (hevos)karavaanikauppateiden ja rannikolta sisämaahan Tiber-jokea johta- vien merikauppareittien risteyksessä. Rooma kappasi kuitenkin muiden heimojen avulla vallan emämaaltaan ja tasavaltalaisen Rooman valtion valtiomuoto luotiin luotiin näiden heimojen hallintokompromissin tuloksena. Latium tarkoittaa tasaista, latteaa maata erotukseksi vuoristosta. Pääkaupunki oli ensin samaa tarkoittava Lavinium.

Kaikki harmaan sävyillä merkityt kansat ovat latinalaisten läheisiä kielisukulaisia. Saappaanvarren alueet muodostavat heimoliiton. Rooman, hyvän asiakkaan (?) pussiin pelasivat aina myös sicelit ja veneetit. Kun joku ulkopuolinen yritti niitä Roomaa vastaan usuttaa, kuten esimerkiksi Hannibal molempia, seurauksena oli juonittelijalle katastrofaalinen operaatio.

Latinalaiset tunsivat tarut Troijan sodasta ja väittivät kuninkaansa Aeneiaan osallistuneen siihen (Troijan puolella, ei siis Kreikan). Nimi Rooma tulee kantaindo- euroopan ”(ylä)virtaa” (ja erityisesti paikka jossa ylävirran kosket muuttuvat rauhalliseski joeksi) tarkoittavasta sanasta ”*s-rem-”, josta tulee mm. – yllätys – suomen Rauma, liettuan sraumė̃ , latvian straume = hidas virta, srūti (srū̃va, srùvo), vanh. *s-remti > *srauti (srauna, srovė).

Etruskin kielessä on tosin sana ruma = pieni, vähäpätöinen, mutta Rooma ei ollut tuota ennen edes ruma tai vähäpätöinen, vaan se oli syntynyt vain tuon ajan uusien teknologioiden pohjalta. Liivissä on muuten myös viroon jälkimmäisessä merkityk- sessä lainattu sana ”rumali”, joka tarkoittaa roomalaista ja kauheata ahmattia suursyömäriä, jollaisia roomalaiset taatusti bileissä olivat silloin, kun muutkin kuten vieraat saattoivat päästä heitä näkemään. Heidän, sanotaan katurahvaan (populus) ja orjien täysin arkipäiväinen hengissä pysymisruokansa jossakin sisämaan kaupun- gissa kuten Roomassa oli nimittäin niin huonoa ja pahaa ja vaarallistakin, että sitä syötiin mahdollisimman vähän ja harvoin: ”keskitysleiriruokaa” kuten pilaantunutta kalaa ja bileistä yli jäänyttä lihanroiketta, ruohoa, juuria, jauhonkyrsää, joiden maku häivytettiin hapansilakan (hapanmakrillin) liemellä, joka on siedätettävä aine, joka sitten, kun siihen on bakteerikanta tottunut, pitää aisoissa vaihtelevammat pöpöt. Tällaisia ruukkuja täynnä ollut laivanhylkykin on löydetty. Liha ei pysy kuumassa ilmanalassa suolattunakaan kunnossa: muutenhan mereen kuolleet elukat eivät mätänisi…

Etymology of the ethnonym Veneti

The ethnonym would then be etymologically related to words as Latin venus, -eris ’love, passion, grace’ and in later forms ’beloved, friendly’; Sanskrit vanas- ’lust, zest’, vani- ’wish, desire’; Old Irish fine (< Proto-Celtic *wenjā) ’kinship, kinfolk, alliance, tribe, family’; Old Norse vinr, Old Saxon, Old High German wini, Old Frisian, Old English wine ’friend’, [3] Norwegian venn ’friend’. The name ”Wends” was a historical designa- tion for Slavs living near Germanic settlement areas. Also, the word wend meant water in the Baltic Old Prussian language suggests that the Wends were those who lived by the water or waters. [4] In the Esto- nian and Finnish names for Russia — Venemaa and Venäjä — possibly originate from the name of the Veneti. [5][6]

According to the 20th century linguist Julius Pokorný, the ethnonym Venetī (singular *Venetos) is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *wenh₁-, ’to strive; to wish for, to love’. As shown by the compara- tive material, the Germanic languages may have had two terms of dif- ferent origin: Old High German Winida ’Wende’ points to Pre-Germanic *wenh₁étos, while Lat.-Germ. Venedi (as attested in Tacitus) and Old English Winedas ’Wends’ call for Pre-Germanic *wénh₁etos.

Venus on latinaa ja tarkoittaa veneettinaista. Se sai jumallattaren hahmon kreikkalaisten Afroditelta, kun roomaliset sotilaat ja muut kyllästyivät kotilieden jumalattareen Vestaan, joka symboloi erilaisen tavaran keräämistä kotiin (ja ”istui aarteensa päällä”…). Vestan ruuista jo olikin puhetta. Sen sijaan Venus näytti ainakin taiteessa aina käristävän hiekkarannalla jotakin peuranpyllyä tai keittelevän jotain mereneläviä ja sekoittelevan viiniä vähissä vaatteissa.

Bretagnen venetit: Veneti (Gaul)

Bretagnen etelärannalla asustanut purjehtijaheimo venetit,joita roomalaiset pitivät keltteinä (vaikka eivät erottaneet esimerkiksi germaaneja ja kelttejäkään, erottelu perustui enempi paikkaan kuin kulttuuriin) liittoutui Gallian sodassa 76 e.a.a. Julius Caesarin kanssa, mutta Caesar petti heidät.

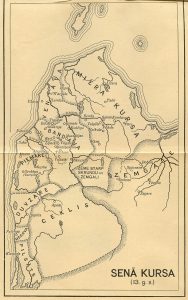

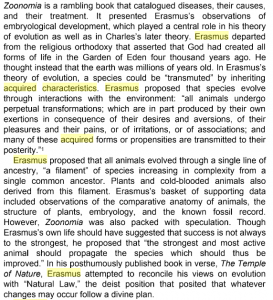

Map of the Gallic people of modern Britanny :

Venetit keskellä sinivihreällä.

Näiden venettien spesiaaliala oli pronssin valmistuksessa tarvittavan tinan kauppa, jota he toivat Britannian Cornwallin kaivoksista. Miten tämä tina lähti satamasta eteenpäin ja minne? Näistä tunnetaan merenkulkupuoli, koska Caesar on sitä kuvannut, mutta heidän kolikossaan laukkaavat hevoset.

Nimi Anglia on muuten preussia ja tarkoittaa ”Hiilimaata”, lt. anglis , lv. uogle = hiili.

The Veneti were a seafaring Celtic people who lived in the Brittany peninsula (France), which in Roman times formed part of an area called Armorica. They gave their name to the modern city of Vannes.

Other ancient Celtic peoples historically attested in Armorica include the Redones, Curiosolitae, Osismii, Esubii and Namnetes.

The Veneti inhabited southern Armorica,along the Morbihan bay. They built their strongholds on coastal eminences, which were islands when the tide was in, and peninsulas when the tide was out. Their most notable city, and probably their capital, was Darioritum (now known as Gwened in Breton or Vannes in French), mentioned in Ptolemy’s Geography.

The Veneti built their ships of oak with large transoms fixed by iron nails of a thumb’s thickness.They navigated and powered their ships through the use of leather sails. This made their ships strong, sturdy and structurally sound, capable of withstanding the harsh conditions of the Atlantic.

Judging by Caesar’s Bello Gallico the Veneti evidently had close relations with Bronze Age Britain; he describes how the Veneti sail to Britain. [1] They controlled the tin trade from mining in Cornwall and Devon. [2] Caesar mentioned that they summoned military assistance from that island during the war of 56 BC. [3]

Julius Caesar’s victories in the Gallic Wars, completed by 51 BC, extended Rome’s territory to the English Channel and the Rhine. Caesar became the first Roman general to cross both when he built a bridge across the Rhine and conducted the first invasion of Britain.

Caesar reports in the Bellum Gallicum that in 57 BC, the Gauls on the Atlantic coast, including the Veneti, were forced to submit to Caesar’s authority as governor. They were obliged to sign treaties and yield hostages as a token of good faith. However, in 56 BC, the Veneti captured some of Julius Caesar’s officers while they were foraging within their regions, intent on using them as bargaining chips to secure the release of the hostages Caesar had forced them to give him. Angered by what he considered a breach of law, Caesar prepared for war.

Sllavilaset (?) vendit

Ensimmäinen teoria, joka yhdisti nuo väestöryhmät, oli germaaninen teoria slaavilai- sista vendeistä, jota nimitystä käytettiin germaanien toimesta kansainvaellusten ajan jälkeen 600-luvulla läntiseenkin Euroop- paan levittäytyneitä länsislaaveista, joiden heimojen omia nimiä olivat olivat mm. obotriitit ja wiltzit. Teoriaa kannatetaan vieläkin.

Slaavilaisten wendien asuttamat alueet 1100-luvulla.

Eräillä keltiiläisillä kielillä vendien nimi oli finn tai fine,millä ei tarvitse olla Suomen vieraskielisen nimen kanssa yhteyttä – mutta täysin mahdotontakaan sellainen ei ole.

Vendit (Baltia)

Vendit olivat heimo nykyisen Latvian Cēsisin alueella.Tutkijoiden parissa ei ole täyttä varmuutta siitä, olivatko vendit slaaveja vai suomalais-ugrilaisia. Vendi-nimitystä on käytetty monista slaavilaisista kansoista, mutta monet tutkijat uskovat heidän puhuneen suomalaissukuista kieltä. Ensimmäinen maininta heistä on Henrikin Liivinmaan kronikassa, jonka mukaan he olivat alun perin asuttaneet Ventajoen aluetta Kuurinmaalla, mutta kuurit olivat karkottaneet heidät nykyisen Riian alueelle ja edelleen Cēsisin alueelle, jossa asui heidän lisäkseen latgalleja. Vendit käännytettiin kristinuskoon rauhanomaisesti vuonna 1206 ja sen jälkeen he taistelivat Kalparitariston puolella Baltian pakanakansoja sekä venäläisiä vastaan.

Liivinmaan riimikronikassa vendeihin liitetään mahdollisesti Latvian lipun syntytarina. Kronikan mukaan vendien alueelta Cēsisistä tulleet sotajoukot toivat tullessaan valko-punaraitaisen sotalipun. ”

Ventavan alue Venta-joen suulla katsotaan vendien/veneettien vanhaksi alueeksi. Venta-nimeä pidetään kelttiläisenä, se tarkoittaa ”keskusta ja pääkaupunkia” (mm. Winchester) ja liettuassa siitä johdettu vieta tarkoittaa ylipäätään paikkaa.

A. Krūkas glezna ”Cēsis — Latvijas karoga šūpulis 1279. g.”, kurā mākslinieks mēģinājis rekonstruēt latgaļu 13. gadsimta karogu.

Latvian vendien lippu, eli nykyinen Latvian lippu 1200-luvulla Cēsisissa (maalattu tuolloisen kronikan mukaan). Lippu on vahvasti Rooman ve- neettien mallin mukainen, ja on sitten useilla paikkakunnilla palautettu esimerkiksi kaupunkilipuksi. Rooman veneeteillä on valkoisen raidan sijasta valkoinen risti (mikä saattaa johtua kristinuskosta), jota on edelleen ehkä tyylitelty:

Triesten, Oderzen, Padovan, Vicenzan,

https://www.tiede.fi/comment/2604624#comment-2604624

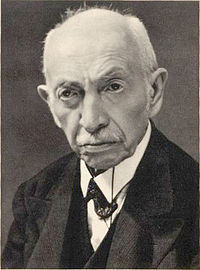

Puolan kielen etymologi Aleksandr Brükner (1856 -1939) esitti, että Rooman ja Baltian veneetit ovat samaa alkuperää, jonka hän arveli olevan lähellä kantaidoeurooppaa.

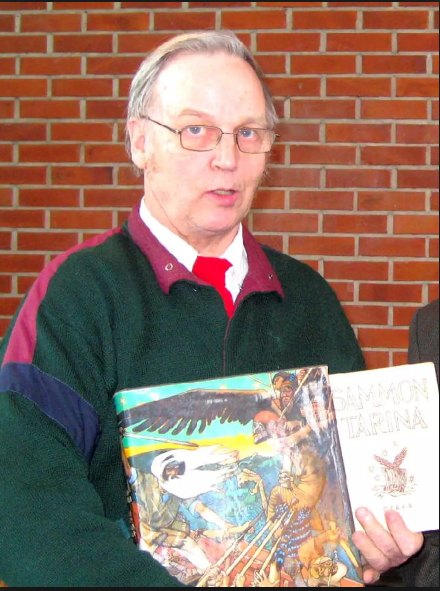

Aleksandr Brükner

” Though Jordanes is the only author to explicitly associate the Veneti with what appear to have been Slavs and Antes, the Tabula Peutinge- riana, originating from the 3rd–4th century AD, separately mentions the Venedi on the northern bank of the Danube somewhat upstream of its mouth, and the Venadi Sarmatae along the Baltic coast. [17] ”

Sarmaatit saivat nimensä ”lisko(nnäköiset) ihmiset” käyttämistään kaviohaarnis- koista. Myös heidän kielisukulaisensa alaanit käyttivät sellaisia käydessään hevos-karavaanikauppaa Persian ja pohjoisten alueiden välillä. Venadi Sarmatae tarkoittaa ”liskonnäköisiä (sarmaatin näköisiä) veneettejä”: se tarkoittaa todennäköisesti sitä, että myös veneetit käyttivät ainakin joissakin vaiheissa sellaisia. Kaviohaarniskalla on sellainen ominaisuus, että se torjuu metalliskärkisiä nuolia ja keihätä, ja jopa miekanpistoa sitä paremmin, mitä terävämpiä nämä ovat. Sittemmin viikinkimiekkojen kärjet tetiinkin paksuiksi ja pyöreiksi: ei katkennut ja lumpsahti haarniskan suojen tai kavioiden välistä.

” Henry of Livonia in his Latin chronicle of c. 1200 described a tribe of the Vindi (German Winden, English Wends) that lived in Courland and Livonia in what is now Latvia. The tribe’s name is preserved in the river Windau (Latvian Venta), with the town of Windau (Latvian Ventspils) at its mouth, and in Wenden, the old name of the town of Cēsis in Livonia. The fact that 12th century Germans from Saxony referred to these people as ’Winden’ suggests that they were Slavs. [18] (See Vends). ”

.

Puolalainen slavisti Aleksandr Brückner esitti, että Venta on kantaindoeurooppaa ja latinaa lähellä olevaa veneetin kieltä, joka kuului kelttiläis-romaaniseen kieliperheeseen. (Tosin eräät venäläiset lähteet arvelevat väiden Roomankin veneettien olleen länsislaaveja.)

http://etimologija.baltnexus.lt/?w=Venta

https://www.tiede.fi/comment/1445254#comment-1445254

Max Vasmer (1886 – 1962)

Venäjä etymologit Max Vasmer ja tämän teosten toimittaja venäjäksi akateemikko Oleg Trubatšëv myötäilevät Brükneriä:

Brüknerin tulokset hautautuivat erilaisten pseudoteorioiden humuun, joissa usen haettiin ”hienoja” kieli- ja muita sukulaisia esimerkiksi antiikin tai Raamatun kielten ja kansojen joukosta – tai eräät toiset mahdollisimman kaukaa niistä. Brüknerin asennoituminen on kuitenkin päinvastainen: hän kyseenalaistaa ”omilleen” rakkaan oletusarvon, jonka ainoana kilpailijana on kai ollut, että Rooman veneetit olisivat olleet latinalaisia ja että muunimien yhtäläisyys on sattumaa ja ”yleistä indoeurooppaa”.

UUSI TEORIA ESITTÄÄ TODISTEITA VENEETTIEN KIELEN LÄHEISISTÄ SUHTEISTA SUOMALAIS-UGRILAISEEN KIELIKUNTAAN

Tässä yhteydessä on kuitenkin sanottava, että kirjallinen historiallinen aineisto on tieteyllä tavalla rajoittunutta: se koostuu paikannimien ja lainojen lisäksi sakraalisista, pappien jumalille kirjottamista tekstinpätkistä. Voidaan mm. kysyä PUHUIVATKO PAPIT TEMPPELITOIMISSAAN JA KANSA SAMAA KIELTÄ – vai puhuivatko papit liiviä ja kansa esimerkiksi kelttiä?

Anders Pääbo (mahdollisesta sukulaisuudesta neandertalin ihmisen genomin selvittäjän Svante Pääbon kanssa ei tietoa) yhdistää myös asiaan aiheettomasti pohjois-Euroopan varhaisimman Maglemosen kulttuurin. Se edustajat eivät puhuneet uralilaista kieltä, vaan sellainen on tullut idästä samoihin aikoihin, kun Maglemosen kulttuuri on lakannut. Maglemoset tunsivat piikiviterät (sellaisella voi ajaa partansakin) ja liikkuivat yhdestä puusta koverretuilla ruuhilla. Veneetit kävivät meripihka-,pronssi- ja muiden arvotarvikkeiden kauppaansa kaviohaarnikoiduin hevoskaravaanein kuin alaanit idempänä.

http://www.paabo.ca/papers/veneticgrammar+dots.pdf

The Language of the Ancient Veneti

A DESCRIPTION OF VENETIC PRONUNCIATION AND GRAMMAR

Two papers from chapters in

“THE VENETIC LANGUAGE

An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL”

(rev 6/2015)

Andres P ä ä b o (Ontario, Canada) www.paabo.ca

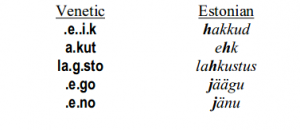

The following papercovers two subjects how Venetic was written and how it was pro-nounced, and Venetic grammar and comparison with Estonian and Finnish. Both are from the full document.

“THE VENETIC LANGUAGE

An AncientLanguage from a New Perspective: FINAL”

The pronunciation draws fromexisting academic decisions about how the Venetic writing sounded, but I add my own discovery that the dots are phonetic markers, mostly signaling palatalization. The grammar description isthe result of my lengthy analysis of the Venetic inscriptions described in the above document which approached the Venetic inscriptions directly instead the traditional approach of making assumptions and forcing the assumptions into the inscriptions. The proper methodology should not involve any existing language, but conclusions should be reached from the inscriptions themselves, from their context in the archeological information and within sentences themselves. Originally one gets simple results like‘Man –duck– elder’, but one keepsan eye on the grammatical endings and looks for consistent meanings. Thus the methodology did not project any known language onto the Ve-netic. However,once it was clear Venetic was Finnic, I began to take notice of parallels in Es- tonian and Finnish and discovered some major grammatical endings were close to the same. In languages, grammar changes most slowly, andthat is why more distant languages will still be similar in grammatical features. And that is also why for any suggestion that Venetic was genetically connected toEstonian or Finnish, we MUST find similarity in grammar.

2PART ONE: PRONUNCIATIONHOW VENETIC SOUNDED

A New Interpretation of the Dots in Ancient VeneticInscriptions, and Resulting Phonetics

Andres P ä ä b o (Apsley, Ontario, Canada)

ABSTRACTIn northern Italy we find several hundred short examples of writing by an ancient people the Romans called Veneti and Greeks Eneti. Written mostly in several centuries after 500BC, these inscriptions borrow the Etruscan alphabet, but use it to write continuously, and with dots inserted into the text in a frequent manner that does not represent word boundaries like dots didin Etruscan and Latin. Traditional studies of the inscriptions have regarded the dots as somekind of syllabic punctuation, and the explanation of how they work is not believable because human nature requires that this dot punctuation be as easy or easier to handle than the word boundary marking of Etruscan, of which the Venetic must have been aware. This paper offers apractical alternative – that these dots are actually phonetic markers mainly marking palatalization but also other phonetic behaviour all of which involves a rai-sing of the tongue. This concept is a very good one because the use of dots has to be simple enough for anyone to use. In this case, the scribe simply inserted them wherever there was some kind of tongue-action of any kind.These dots were enough for the reader familiar with Venetic to be able to read it properly.

Interestingly the Venetic writing allows us to actually reconstruct how the language sounded. Comparing words in today’s highly palatalized Livonian with mildly palatalized Estonian, gives us some insight into how the dots modified sounds. The author also proposes the theory that the Venetic, lying at the bottom of amber trade from the Jutland Peninsula was identical to the ancient Suebic language at the source of the amber, and that the palatalizationand stød of modern Danish ultimately comes from it.

______________________

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Phonetics determined from Latin and Etruscan

In northern Italy we find several hundred short examples of writing by an ancient people the Romans called Veneti and Greeks Eneti. Written mostly in several centuries after 500BC, these inscriptions borrow the Etruscan alphabet, but use it to write continuously, and with dots inserted into the text in a frequent manner that does not represent word boundaries like dots did in Etruscan and Latin.

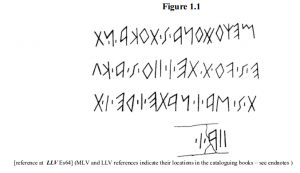

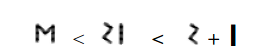

Figure 1.1 shows a very good example of Venetic writing. In small case Roman text below itwe see the text transformed to a form we can read, using Roman alphabet phonetics.

[reference atLLVEs64]

(MLV and LLV references indicate their locations in the cataloguing books – see endnotes)

megodona.s.toka.n.t|e.s.vo.t.te.i.iio.s.a.ku|t.s.$a.i.nate.i.re.i.t|iia.i.

Venetic text is read in the direction the characters are pointing, in this case right to left. When it gets to the end of the line it goes to the next, starting at the rightagain. In other inscriptions theletters may simply turn and come back – one follows the direction the letters (such as the E) arepointing. The convention of writing down Venetic text in Roman al-phabet is to write them in Roman alphabet small case, in themodern left-to-right, adding the dotsin their proper places. New lines, changes in di-rection, continuation on the other side are shown with a ver-tical line. In reality these new lines or changes in direction mean nothing. It is done purely from the scribe running out of space. Mostly they are irrelevant to reading the script. Often they do not even respect word boundaries – as if the scribe did not even have a concept of word boundaries butwrote what he heard – which sometimes resulted in variations in spel-ling and dot-handling. Notein the above example the dots appear almost like short I’sand that may be how the practice gotstarted – trying to write pala-talizations with short I’s The Ancient Veneti borrowed the Etruscan alphabet for their writing and then modified it – mostly from introducting dots. From the relationship between Etruscan and Roman Latin in thesame area, and other factors, the sounds of the Etruscan alphabet are quite reliably understood,and we can assume that when Veneti adopted the Etruscan alphabet they also adopted its sounds.But in my new view of the matter, they then modified those sounds by adding dots before andafter some letters as needed. We cannot argue too much against how Venetologists in the past have decided on the sounds of the Ve-netic alphabet. I only found a couple of issues. Therefore other than offering my summary of the most common Venetic letters in figure 1.1, we need not discuss the phonetics ofthe Venetic alphabet further.

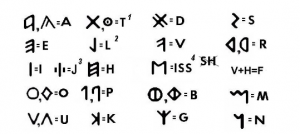

Figure 1.2

THE BASIC VENETIC PHONETIC ALPHABET WITH ROMAN EQUIVALENTS

(with small modifications from current thinking)

NOTES ABOUT SMALL ISSUES (discussed later)

1 – The X-like character is most common, but in the round stones of Padua, the T is represented by a circle with a dot inside.

2 – The L-character we think sometimes has a form that can be confused with one of the P-characters. Watch for two possibilities insome inscriptions.

3 – Traditional Venetic interpetations have assumed that the I with the dots on both sides is an “H”. This is correct only if the H has a high tongue, as it is an ‘over-high’ “I”. It actually sounds either like a “J”(=”Y”) or an “H” depending on surrounding phonetics.

4 – I believe that the big M-like character is probably an “ISS” as in English “hiss”, and not really the “SH” (š)that has been assumed. We show it when transcribed into Roman small caps form with $.

The main purpose of this paper is to solve the mystery of the dots found in the AncientVenetic inscriptions.

1.2 The Mystery of theDots in Ancient Venetic Inscriptions

Traditional studies of the inscriptions have regarded the dots as some kind of syllabic punc-tuation, and the explanation of how they work is not believable because human nature requi-res that this dot punctuation beas easy or easier to handle than the word boundary markingof Etruscan, of which the Venetic must have been aware.Originally ancient writing by Etruscans and Veneti were written continuously without any punctuation, but that made it difficult to read. You had to sound out the letters and then try torecognize the words. The Etruscans solved the problem by using dots to show the word boundaries. Romans followed the practice, and then the dots disappeared and there were spaces.However, for some mysterious reason, the Veneti did not try to explicitly show word boundaries. They began putting dots on either side of a letter. Through the years academics attempting to interpret the Venetic inscriptions puzzled over these dots.

According to the accepted explanation, the dots were used to separate the final consonants from preceding phonological units, but was not present between a consonant or aconsonant (obstruent+sonorant) group and a following vowel (monophthong or dipthong), giving a syl-labic form C(C)V(C) which then underwent changes due to weakening and loss of h- (*ho.s.ti.s. > *.o..s.ti.s.) and syncope of i preceding a final fricative (*.o..s.ti.s. > *.o..s.t.s.). As nice as it may be to present to understand the linguistic shifts in a language, we must not forgetthat the number of in-stances of Venetic inscriptions is limited. It is not enough to iden-tify a few ‘proofs’ of a theory, as that can simply be an arrange-ment of a few instances of coincidences that seemto demonstrate a pattern. But let us berealistic. Let us imagine the language being in actual use, and being spoken in many dialects and being interpreted in writing in different ways. Forexample, how do we know that .o..s.t.s. came from .o..s.ti.s. Maybe it did, but maybe .o..s.t.s.wassimply from laziness.

Consider your modern language.How often do you see vowels of consonants dropped by different speakers.For example someone says “DIFFRENT” in-stead of “DIFFERENT”. Venetic suffers from having been written continuously and there being sofew examples (less than 100 complete senten-ces, not fragments) The overly intellectua-lized assumptions of linguistic shifts and patterns come from imagining that Venetic writing was highly standardized and formalized so that every-one spoke it in exactlythe same way or wrote it in exactly the same way.

But is that assumption realistic. We have to allow for the more natural in-terpretation as sug-gested from the use of writing in Greece and elsewhere – that it was not exclusive to some priestly class but something that inspi-red everyone. Even if writing was only available to the educated, even among the educated dialects varied. Thus if we take the more realistic view, that Venetic writing developed, as it did elsewhere, asa popular fad – something that pre-served sentences or made objects speak – then we have toapproach the entire subject of the Venetic inscriptions from the point of view of it being something easy to master. You had your basic sounds – the natural vowels and consonants formed by the mouth in the most natural positions – and then you had to modify it here and therewith intonations, stresses, pauses, and other effects such as palatalization, trills, etc. One way ofidentifying the depar-ture from the most natural human sounds, is by adding punctuation. Imaginea modern lin-guist trying to record a language he does not know. He will write down the soundsin phonetic writing, and add punctuations for stress, length, etc. It seems to me that if thisapproach of capturing the sound of speech is soobvious today, that it would be obvious inancient times.

Identifying word boundaries like we do today, helps us read because all languages have con-sistent patterns for word units. For example, stress may always be on the first syllableon a word. There may be length and pause features too. But in order to read writing that only shows word boundaries, you have to already know the language. Phonetic writing simply reproduces the speech, and the writer does not need to know the language at all. Thus what if the Venetic dots represent phonetic punctuation.Yes,even if the linguists’ ob- servations about many of the dots locations are correct, their explanations are merely a byproduct of the way the language is spoken. Let’s say that Venetic always palatalizedan “S” sound before a “T” as in dona.s.to Then the dots obviously have arelationship to sounds before and / or after. But it is absurd to imagine that the purpose of the dotsare to identify the word boun-daries indirectly. It makes more sense that dots were added aroundan “S” in that en-vironment simply because that was how they spoke it. There is a similar word lag.s.to that shows it again. Certainly we can find some examples in which a pat-tern is repeated. But it is much much more realistic to imagine aword of Venetic speakers whose only aim was to reproduce the sound of sentences they spoke, and they knew nothing about word boundaries, case endings, syllables etc. They were simply aware that the alphabet represented sounds, andthe dots were a phonetic punctuation device. Note that even today, you can ask a child who has only learned the sounds of Roman letters, to write a sentence he has never written before. He will sound it out and it will be readable, evenif it did not follow the conventional spellings that have developed in the modern language.

The phonetic writing explanation for the dots is so natural, that already it is convincing even beforelooking at examples. If the Veneti were long dis-tance traders – as suggested by their being agents of northern amber and having colonies at the ends of Europe – then here is a practical reason for phonetic writing. They could record important phrases of customers with-out knowing anything about thewords and grammar. Phoenicians are known to have created such phrasebooks, and if Veneti were traders in the north and major rivers,someone may have borrowed Etruscan writing, and then added the dots for phonetic punctuation. It is known that the dot punctuation appeared fromabout 300BC, but that is about the time the Veneti reached their zenith with the colony at Brittany, and their role in carrying tin from the British Isles.

1.3 Raw Phonetic Writing vs. Word-Boundary Writing

Ancient peoples generally wrote down sounds in order to reproduce what was spoken as closely as possible. In the beginning – as seen even in early Etruscan – there was nothing elsethan a string of letters representing sounds. But, given the variation in any language of stress, emphasis, length, pause, etc that was not enough. For example how should we read this? Obviously if you know the language, you can read the string out loud and recognize the words: how should we read this? And that was the case with early Etruscan, and some early Venetic too. A continuous sting of let-ters was not enough. One had to read it out loud over and over beforeone realized what it was saying. Thus there was wisdom in adding something to the string of sounds in order to give the readersome guidance.One way was to mark every sound feature–pauses, intonations, etc. Raw phonetic writing.The other way, was to use the trick with which we are familiar today, to show wordboundaries. Identifying word boundaries exploited the fact that in language words are spoken inconsistent ways. For example the lan.-guage mayalways emphasize the first syllable. Thus if youknew the word boundaries, when you read it,you would emphasize the first syllable, and thesentence would be read correctly; but you had to already know the language. Let us look at each approach in more detail.

1.3.1. Raw Phonetic Writing

Phonetic writing, thus began in the raw form that recorded everything, Like the modern elec-tronic recorder does, it doing nothing to simplify the text and the reading of it. The earliest phonetic writing was purely recording what the spoken language sounded like. Phoenician andother trader peoples, recorded common phrases in the language of their customers in a rawphonetic fashion so that when needed they could read it back. They did not have to know anything more about the language. Similarly, a modern linguist who does not know a language will write it down in a raw phonetic fashion too, exactly what he hears, using the modern standard phonetic alphabet.

7

Not knowing where the word boundaries are, they will add marks to indicate length, pauses, emphasis, etc. This is raw phonetic transcription. Other than the few inscriptions done in the Roman alphabet following Roman conventions(like the Canevoi bucket inscription), Venetic writing, has the hallmarks of raw phonetic transcription: It is written continuously and filled with dots that seem to function like themarkings a linguist makes when transcribing speech phonetically. ThusVenetic inscriptions can be viewed as transcription of what is actually spoken, using thedots as an all-purpose marker for pauses, emphasis, length, etc.Because the written Venetic language was not standardized, this dot-device must have been a very simple intuitive tool. I believe the rule was that dots were applied where some kind of tongue-related feature (mainly palatalization) was applied in the speech. Such a simple concept – a dot-marker serving many purposes – was something that could easily be applied and understood by anyone. One may wonder why the Venetic writing was written inthis way,when the option ofmarking word boundaries would have made it easier. I suggest that perhaps Venetic was so highly palatalized that the Veneti wanted to mark those palatalizations even if it was not ne-cessary to do so. But there is another explanation. If the Veneti originated as traders, then it was very important to record the languages of customers. The problem with word boundary writing is that it relies on the reader already knowing how the language was spoken – where the inflections, stresses, lengthenings, palatalizations, etc were applied. For example while Latin wasused throughout the Roman Empire we have no idea from Roman texts how it actu-ally soundedwhen spoken in different places and times in history. Like English today, there could have been many accents/dialects.

Word boundary writing does not capture the sound of the actual speech. Word boundary wri-ting is fine if you already knew the language, but if you neededphrasebooks to use in foriegn markets, you needed to record a whole phrase (such as ‘Would you like to buy this beautiful necklace?’) without needing to know how it broke down into words.In that case, the phrase had to be written down completely phonetically – a continuous string ofsounds, with marks used to indicate pauses, emphasis, etc. Perhaps the dots were such phonetic markers, which became guides to how to speak the whole sentence, without having any idea about what were the words and grammatical ele-ments within it. If writing was used by traders, it did not have to be carved in stone or bronze. Thus, the writings archeology has found on stone, bronze and ceramics in the earth may thus be only thetip of the iceberg. How much more is there that has disappeared because it was written on paperor other soft media? For example Phoenician practices included not just writing on paper, butalso on wax tablets that could be melted and reused.

Remains of Phoenician writing tablets which originally contained wax and was written upon by styluses. Note it has a hinge in the middle, and the user could fold it up and slip it into his pocket. If the Veneti used such wax tablets, a great deal of writing may have been done that has been lost.

Writing on wax, paper and other perishable media would not have survived for archeologists to find. We do not have here a situation such as existed in ancient Sumeria, where all everyday writing by every-one was done onto flattened pieces of clay, resulting in the survival in the earth of many thousands of cuneiform clay tablets of usually mundane content, such as inventories of goods and shopping lists.

1.3.2 Word-Boundary (Rationalized) Phonetic Writing

While we write texts (like this sentence) with blank spaces between words – and Romans and Etruscans used dots – in speech these spaces do not appear as pau-ses. They are there mainly to assist the person who knows the language in reading it, without the need for detailed phonetic punctuation. If we know what the word is, then from our familiarity with the systematic characteristics of the language,we place all the stress, emphasis,etc in the right places automatically. It simplifies the phonetic writing. Furthermore, with word boundary shown, the readers could also view the word as a graphic symbol. The only drawback of writing using word boundaries, is that the reader has to already know the language to reproduce it properly, whereas raw phonetic writing could be read as it sounded by any reader.1

Among the Venetic inscriptions, the Canevoi bucket example given earlier, is a rare instance where Venetic was written in the Roman fashion, with dots serving as word boundaries in the Roman fashion, rather than indicating phonetic features. Note that when the Venetic was written in the Roman fashion, there was no more need for the dots. This helps confirm that the dots were phonetic pronunciation guides when writ-ten continuously, and were no longer necessary for those who knew the language, once word boundries were defined

1 This makes Venetic writing, using the dots, extremely valuable – it allows us to reproduce the actual sound, once we know more about the use of the dots.

8

2. VENETIC DOT-PUNCTUATION TO IDENTIFY PALATALIZATION?

2.1 Some Evicence Venetic was Extremely PalatalizedThere is some periferal evidence that Venetic was highly palatalized. There exists a basic truth that when a people begin speaking a new language, they will speak it in the manner of their ori-ginal language. We call this an “accent”. In our theory, the Veneti were long distance traders, and the Veneti of Brittany were part of their trade system. With the rise of the Roman Empire, this trade system collapsed and different parts of the system as-similated into their surrounding peoples.At Brittany the Veneti assimilated into Celtic.

If their original Venetic language was palatalized, then their Celtic would also be palatalized. Without having another standard to emulate, this accented manner of speaking Celtic would be passed down from generation to generation. Called the Vannetais dialect of Celtic, it stands out from its neighbouring Celtic dialects from being much more extensive palatalization.

Another example would be at the north end of the strong trade route between the Adriatic and the Jutland Peninsula. Today, at the Jutland Peninsula we find Danish. Danish is a highly palatalized German. Was the original language highly palatalized, and was the palatalization transferred when the people assimilated into the Germanic of their military conquerors.

2.2 Dot-punctuation – Invented to Indicate Palatalization?

Venetic writing borrowed the Etruscan letters, but did not acquire the Etruscan me-thod (later used by Romans too) of marking word boundaries. Instead, Venetic wri-ting simply began to add dots to the original continuous stings of letters. These dots have puzzled analysts of Venetic for centuries. They realized that it was a scheme to make the continous text easier to read than continuous writing without any spaces or markings, and proposed it was a “syllabic punctuation” and that the reader deter-mined the word boundaries from it. On the other hand there are also analysts who – failing to figure it out – like Slovenian analysts, claim that the dots are all decorative and meaningless. From the point of view of the probability bell curve, such a claim, although possible is not probable. In our methodology everything has to be very realistic, natural, and acceptable, and bizarre interpretations – according to the bell curve – have to be so rare they are negligble. The most natural answer, the most probable answer, is that the markings were intended to mark something strongly evident in Venetic, but absent in Etruscan.

I realized it had to be something very simple, not requiring special education for either reading it or writing it. But it could not be mere decoration either. That would be utterly silly as decorations are an aesthetic matter and if it were true then every scribe would put the dots in slightly different locations for the same word, and even employ other decorations too. This did not happen. For example dona.s.to always had the dots around the .s. and the n never had dots for this word but it appeared in other words –the dots were clearly purposeful. But they had to be practical and easy to apply. They had to be at least as easy to apply as the word-boundary dots they saw in their neighbouring Etruscan.

It is obvious how in Etruscan and Roman texts the dots were word boundaries which the scribe could easily insert from either small pauses in actual speech, or an under-standing of where words began and ended. But what simple feature could the dots in Venetic represent? What could there be that any writer or reader could understand almost intuitively without any major formula needing to be applied?

10

And why dots? What would dots represent? Maybe they were not dots initially but small “I”s. A good way of indicating palatalization might be to put small “I”s at front and back of a sound. For example N > iNi I noted that the dots in the inscription reproduced above in Figure 1.1 look like short “I”s.

Looking at the real world of languages, I noted the differences between written Esto-nian and Livonian. Livonian is probably descended from the same east Baltic coast lingua franca of a millenium or two ago, but Livonian has been subjected to influence from the Indo-European Latvian language for the last half millenium or more. I no-ticed that while Livonian had words similar to Estonian,they were more extremely pa- latalized. The extreme palatalization has prompted the written Livonian to develop a host of letters officially described as palatalized. (In Estonian palatalization is not ex-plicitly marked but is still there – although the palatalization is not strong. Was that the simple answer? Was Venetic highly palatalized like Livonian was. This palalati-zation would be caused by considerable contact with Indo-European languages that were spoken with tigher mouths. The action also resulted in vowels sounding higher (which we can roughly express by U>O, O>A, A>E, E>I, I>H or ’ break)

The palatalization in Venetic, I proposed, was indicated by dots on both sides of the normal letter, the most important being the “I” where .i. would sound either like “J” (= ”Y”) or “H” with palatalized tongue. But then I saw the dot to be more widely applied serving as an all-purpose phonetic marker. It could alter any alphabetical sound in which the tongue played a role. It could indicate sounds like “SH” and a trilled R, and indirectly even mark a pause or an emphasis or length. This theory made the dots very important to the project. It meant we cannot simply go by the Roman alphabet equivalents. We also have to know how the dots alter the sound. If the use of dots lasted for centuries and was even used by ordinary people writing graffiti, then it had to be a very simple concept –not some complicated formula.

For an English speaker, our best example of palatalization is the ñ in Spanish, but weak palatalization is not uncommon in all languages. Most sounds made by the human mouth can be found in all languages to some degree, even if the language does not explicitly recognize it. For example, although Estonian, unlike Livonian, does not explicitly define palatalized letters, there is weak palatalization where Livo-nian has strong palalatization. Estonian does not indicate the palatalizations, and any student of Estonian has to learn these.

Another modern example of a language that is weakly palatalized in one and strongly in another is Swedish versus Danish. Swedish has the rounded mouth (like Estonian) while Danish is strongly palatalized (like Livonian).

When Venetic was next written in the Roman alphabet for a while, with word boun-daries shown, all these dots were abandoned.. If the reader knew the word bounda-ries, they could insert the proper pronunciation – the palatalizations, etc – from their knowledge of the language. Once I had made the discovery, and knew most of the dots marked palatalization, I began to take notice of the dots around letters which we do not normally palatalize. I discovered that in all instances there was some kind of significance of the tongue. For example .r. was a trilled r.

11

3. CATEGORIZATION OF DOT USE IN VENETIC: RESULTS

3.1 Introduction

The secret of the dots cannot be solved independently of the rest, and the following conclusions were arrived at piece by piece throughout the project of deciphering Ve-netic, as outlined in THE VENETIC LANGUAGE: An Ancient Language from a New Perspective: FINAL. This paper on the Venetic dots is also decribed in its Chapter 4. However they only affect how the Venetic sentences were pronounced and we can describe it independently here, to give the reader an idea of prounciation right off and then not have to deal with them further. As I already said I made a hypothesis that the dots were phonetic markers, and subsequently the hypothesis was proved correct. The most obvious use was to mark palatalization, but it marked more.

The dots, mainly served to indicate the common palatalizations we know well today in languages like Spanish, or more extensively in Livonian and Danish, appeared to have been applied to all circumstances of the tongue and palette being applied. It took me a long time to realize that past analysts have been wrong in claiming the Venetic character that looks like an “M” was a “SH” sound.The “SH” sound obviously has to come from a ‘palatalized’ S. As you will see, I interpret the sound of the cha-racter that looks like an “M” as a long hissing S,possibly with an “I” at the start. Thus, once one grasps that the dots mark any intrusion of the tongue in the souind, questions about the correctness of past interpretations are resolved.

3.2 The “I” with dots on both sides – .i.

The modern custom in showing Venetic writing is to convert the Venetic letters to small case Roman and then to add the dots as well with periods. We begin by consi-dering dots on both sides of the “I” character. According to the bronze sheetsthat re-peat oeka over and over, with each of the Venetic letters attached to the end, the dotted “I”was so common, the Veneti actually recognized it as one of the basic al-phabet letters. As I mentioned, traditional scholars of Venetic inscriptions have de-cided from various evidence, that this new character of the “I” with two short lines on both sides, represented some sound akin to an “H”. A few analysts have proposed a “J” sound. Since some early inscriptions show the dots as short lines, almost like small “I”s there is merit in considering the dots to represent tiny short I’s. (see Figure 1.1) The purpose of that, before and after a sound, in my view is to show palatalization.

These short lines then developed into dots. This truth can be realized when compa-ring the location of some of the palatalized letters in Venetic with locations in other languages. Human speech psychology and physiology is a constant and that means the same phonetic changes can occur in any language independently.

Languages do not change arbitrarily. If we put small faint I’s around an “I” sound we tend to arrive at the “J” which is the same as the sound of “Y” in English usage – short and consonantal. The new character, the Venetic .i., was therefore actually an ‘overhigh’ “I”. Overall increased palatalization in a language can be caused simply by a general shifting, in the manner of speaking, of all vowels “upward” (such as U>A, A>E, E>I, I>Y/J,H)

12

If we explain the .i. in terms of palalizing the “I” we can see that it can result in a “Y/J” sound in one environment and an “H” sound in another environment. Palatali-zing the “I” sound will demonstrate, the resulting sound is a “J”, but following a consonant like “V” it sounds like an “H” too – but an “H” produced at the front of the mouth, not back . Traditional analysis of the Venetic writing has decided (LeJeune) that the v.i. is an “F” sound and v.i. has been rewritten as vh (which occurs else-where in that form). While it may be true that v.i. sound might sound like vh, I disag-ree with the Venetic v.i. always being rewritten vh and assumed to sound like “F”. It was certainly similar, but one must not forget the origins of v.i.r in the palatalization of “VIR” (as I will propose). I think it is wise to leave the .i. alone, write it exactly as written, and not convert in the small case Roman representation into an “H”. Don’t arbitrarily alter what Veneti wrote. If the v.i. sometimes was written with a new cha-racter assumed an “H” and later as Roman “F” well we may be dealing with slight variations in dialect, or the scribe’s habits. In other words the “F” sound could have developed in the dialect from an earlier “VJ” (“VY”) sound – especially when the people began to adopt Latin which had no “VJ”(“VY”) sound.

The simple idea behind putting dots on both sides of letters that everyone could quickly understand was that wherever short I’s on dots were placed on both sides of a letter, the reader simply pushed up the tongue to the “I” positionahead of the sound, and the sound of the letter was altered accordingly, it becoming “J” (“Y”) or “H” according to its environment.

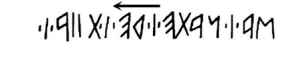

3.3 Dots around the “E” – .e.

The word .e.kupetaris allows us an opportunity to prove the above theory that the dots recorded palatalization. The effect of dots appears to be explicitly demonstrated in IAEEQVPETARS in the following inscription (When we show Roman capitals, it means the original is in the Roman alphabet)

The word appearing as .e.kupetaris in inscriptions in the Venetic alphabet is shown here as IAEEQVPETARS. It is clear that .e.ku sounded like “IAEEQU” as given via Roman alphabet phonetics. Here we see both the palatalization suggested by the “I” and also a lengthening of the vowel. It demonstrates that the all-purpose dot could indirectly mark vowel palatalization but it could mark other modifications in the flow of sound as well such as lengthening or pause. Note in the illustration the IAEEQVPETARS down the right side in smaller letters suggests it is an added tag-line. This has helped us conclude that the word means something like ‘goodbye’ ‘have a good journey’, etc

13.

Figure 3.3

[-GALLE]NI.M.F.OSTIALAE.GALLEN | IAEEQVPETARS

[MLV-134, LLV-Pa6]

See the word IAEQVPETARS down the right side. Note too how it seems added as a tag, one of the reasons for interpreting it as a ‘happy journey’, ‘bon voyage’, etc.

3.4 Dots around Initial Vowels – In General

The above example showed the dots around the intial vowel E proving the palatali-zation.. Similar effects can be expected on the other vowels. We begin with the basic I with dots also discussed earlier. The phonetic representations use Roman pronunciation (J = English Y).

.i. = “J”

.e. = “jE”

.a. = “jA”

.o. = “jO”

.u. = “jU”

Perhaps Venetic put the stress strongly on the first syllable, and this feature may be the result of needing to ‘launch’ the initial vowel strongly. Such a need would pro-duce a consonantal feature at the start –a J/Y or H. This could simply have been a feature arising from the manner of speech, accent, etc, a para-linguistic feature not part of the language itself; but if it was strong, the phonetic writing needed to record it. A good modern example would be that if we found a dialect of English in which all E sounds were pronounced “I”, a writer might want to show it explicitly – especially if writing dialogue – instead of normal writing. For example if there were people who spoke “Hippy Dey ti yeh”, a writer transcribing this might want to write it phonetically as I just did (or in other phonetic writing) instead of writing “Happy Day to you” .

Early phonetic writing was not aware how languages only need certain sounds called “phonemes” in order for the text to represent the language, and therefore early phonetic writing tended towards being literally phonetic, capturing even strong paralinguistic sounds even if they were not part of the language.

Furthermore, if ancient scribes used too few characters for the sounds, a reader who knew the language was still able to read the text. Consider the Livonian language. Linguists have identified many palatalized sounds, and determined that many of them are phonemic; but if Livonian were written without the identified palatalized let-ters, a Livonian would still be able to identify the words. They might however read it more like Estonian where palatalization is weaker and needs not be marked. The reason Livonian has been assigned many additional palatalized letters is largely be-cause of the influence of linguists.In the actual history of written language the written language naturally reduces to a form that is readable, regardless of whether is agrees with linguistic representations. English is a good example – it is filled with letters wherein we cannot tell the sound without looking at the whole word. For example, we can only tell that the word “where” is pronounced with the final e silent, only by recognizing the whole word. Thus the more history there is in a phonetically written language, the more it departs from strict phonetic representation, and the more the reader determines words from experience with the full words: the more the words become their own graphics.

To summarize, early phonetically written language like Venetic, naively tries to record the actual spoken language and captures many features which may not really need to be written down. Conversely there have been many written languages that minimized the alphabet, and the actual sound of the language has been lost. Too much information makes it possible to reproduced the sentences without knowing the language, and too little information requires the reader know the language well enough to identify the intended words even with a lack of information.

In the case of Venetic, therefore, we must recognize that, since the Venetic writing had very little history, for the most part, it is highly phonetic. It is valid to read Venetic phonetically, following the Roman alphabet equivalents, and expect it to quite closely reflect how it was actually spoken. At the height of the Roman Empire it is certain that the way Latin was spoken varied from one region to another while the written language remained unchanged. In other words, the Latin spoken by common folk in Britain would have sounded different from the Latin spoken in Gaul, or Spain. But the Latin would be written the same way. A good example is modern English. Eng-lish is spoken in many different ways, many different dialects – compareaccents in America vs. Britain vs. Australia vs. India etc. All use the same written language. If we were to write English truly phonetically, there would be a hundred or so written forms of English.

If Venetic writing tried to reproduce its language explictly then we can expect dialec-tic variations will appear in the writing. But what is most intriguing is that by adding the dots – serving not just mostly palalization and similar tongue-produced effects but (see later) situations with lengthening (of either sound or silence) –allows us to reproduced Venetic quite accurately.

Even if all the dots were not necessary and word boundary writing could have been used, the Veneti thought that it was important to mark the palatalizations explicitly, maybe thinking that if they didn’t it would be read like Etruscan.

While the dots strictly speaking are not needed for someone who knew the lan-guage, and a Venetic reader could do just as well with dots only marking word boun-daries, if we initially know no Venetic at all, the dots certainly give us a vivid idea of how the Venetic sounded.

Perhaps it sounded like Danish relative to German, or Livonian relative to Estonian. It is a blessing in disguise!! Furthermore as the dialects changed, the scribes who recorded it, captured significant changes in pronunciation. That is why we will see variations on some words, and especially with the application of the dots.

If we regard the Venetic writing as extremely phonetic because of all the dots, we cannot view the variations as erroneous, but that some words were spoken a little differently between two locations and two periods in time. For example if there is an inscription that shows .e.petars instead of .e.kupetari.s. that does not mean the scribe made a mistake. It simply means that, just like in English good-bye can become g’bye, so too a commonly used .e.cupetari.s. could reduce to .e.petars over time.

When Venetic at the beginning of Roman times was written with Roman alphabet letters, the dots vanished, confirming that the original Venetic written language was more a phonetic recording of actual speech than its Roman alphabet form. We also have to bear in mind the fact that Romans explicitly showed word boundaries, which reduced the need for additional phonetic punctuation.

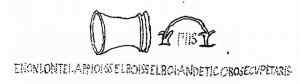

Figure 3.4

9b-B)

9b-B) ENONI . ONTEI . APPIOI . SSELBOI SSELBOI . ANDETIC OBOSECUPETARIS – [container – MLV 236, LLV B-1]

This is one of the few inscriptions (other than Roman writing inscriptions on urns) where Roman letters are used, and the Roman convention of simply using dots to separate words. The dots around letters are missing. This tends to prove that strictly speaking the dot-punctuation was not necessary to read the text. But without the dots, someone who does not know Venetic will read it like reading Latin, and the palatalizations, etc. that reproduce how it was really spoken is lost.

Throughout the investigations of the Venetic writing, investigators have wondered why the word “Veneti” does not appear (other than in one instance Venetkens, which could simply be a borrowing from Latin.) But we must bear in mind both that ancient Latin spoke the V as a “W” and Greeks called them “Eneti” (or “Henetoi”) both of which suggests the word was introduced with a palatalized initial “E”. In my analysis of the Venetic inscriptions I came to the conclusion that in the inscriptions the word is represented in the stem .e..n.no-. For example it appears as .e..n.noniia. The iia ending suggests the Venetic way of saying the Roman “Venetia”

moloto.e..n.noniia

[urn- MLV 91, LLV-Pa90]

Instead of showing any V-character (=W-sound), it shows the E surrounded by dots. The actual Venetic pronunciation of .e..n.noniia may have sounded something like (playing on the phonetics of the Roman alphabet) “WHEI-NO-NII-A”.

This helps us reproduce the sound of other Venetic words that begins with dotted vowels. For example there is one sentence in which the scribe has added plenty of dots – .e..i.k. It must have sounded very unusual, such as WHEIHK, YEIHK, etc.

Note that the above discussion is a good example of determining the meaning of the dots through looking at evidence, starting from our first observation that showed .e.ku sounded like “IAEEQU”. It puzzles me how earlier studies of Venetic writing failed to identify the dots as punctuation that modified normal Etruscan letter sounds, and that it has nothing to do with syllables (which someone proposed.) It is nothing more than added information on pronunciation.The fact that it was added is evidence the Venetic language was pronounced with extreme palatalization – maybe like how Danish or southern Swedish speaks its Germanic language today – and the Venetic scribes were motivated to introduce the dots simply because their language was extremely different from the pure round sounds of neighbouring Etruscan or Latin.

We will look at the effect of the dots on consonants in the next sections. But first, for comparison, let us look at something similar with respect to intial vowel treatments in Estonian versus Livonian, were Estonian has weak palatalization and rounder sounds like in Latin, while Livonian is extremely palatalized like Danish.

3.4.1 Examples of Palatalization on Initial Vowels in Livonian and Estonian

To illustrate the above phenomenon of consonantal features appearing with intial vowels in a language in which there is stress on the initial vowel, we can look to some examples in Livonian, a Finnic language that was located on the coast south of the related language of Estonian. Perhaps you know of other languages to observe. One might for example look at highly palatalized Danish versus standard Swedish, for example. I use these examples that compare Livonian and Estonian, since my own greatest familiarity is with Finnic languages.

Since Livonian is highly palatalized and Estonian considerably less, it is possible to compare Livonian words with Estonian equivalents, and then compare what we witness with the above described circumstances visible in Venetic initial vowels with dots.

While Estonian does have palatalization it is mild and not explicitly noted in the written language. However, in Livonian, as I say, palatalization is strong and signifi-cant. Livonian explicitly shows the palatalization with diacritical marks. However, this applies only to situations commonly viewed as ‘palatalization’. As I indicate here, the Venetic use of dots seems more broadly applied to all situations in which the tongue modified a sound, and even side effects like length or pause.

Let us see what we can discover from Livonian compared to Estonian. Estonian like Finnish, in putting stress on the first syllable, commonly adds some consonantal feature at the start that helps launch the initial vowel. Note it is impossible not to have something consonantal on an initial vowel, in any language – but usually it is so weak it can be ignored in languages that do not put a stress or emphasis on the first syllable. For example in English, stress is applied later in the word. For example English people will mistakenedly pronounce Helsinki with “HelSINKi” instead of the Finnish “HEL-sinki”.

17

In fact this is a good example of a word in which the initial H probably appeared as a result of the emphasis on the first syllable in Finnish. There are other words in Esto-nian and Finnish where an “H” or “J/Y” has been explicitly recognized. But the con-sonantal sound launching an initial consonant is there, and its strength will vary with the dialect. In the following, we see some examples in which the Livonian is shown with an explicit J at the start, where it is not explicitly noted in written Estonian:

Table 3.4.1

initial vowel Estonian Livonian

E ema jemā

A ära jarā

I iga jegā

(J follows the convention of pronouncing it like English “Y”)

What can we derive from this? It suggests that in pronouncing Venetic too,we should place the emphasis on the first syllable, and this will help us understand the reasons for the Venetic employment of the dots in various locations. Having observed similarities with Finnic intial vowels, we will continue to make reference to other coincidences with Finnic languages.

The reader is always welcome to advance examples of other languages with empha-sis on the first syllable. It is possible that a consonantal launch for initial vowels, is quite common for all languages – not just Finnic – that place the emphasis on initial syllables. The observations in the following sections will probably be found in those as well. The reader is welcome to investigate other languages. Our discussion merely observes phonetic parallels with Finnic purely as examples.

3.5 Palatalization of Consonants.

Besides the vowels, the Venetic inscriptions are also liberally sprinkled with dots on both sides of consonants. On sounded consonants, the resulting sounds are our familiar consonant palatalizations such as the Spanish palatalization of the N written as Ñ. In Livonian the palatalization of sounded consonants L and N involve the use of diacritical marks in the form of a cedilla underneath.Livonian palatalizes the D and T and R and shows it in this way as well, with the cedilla underneath. Other written languages that actually show palatalization,may have other markers. If palatalization is weak and not linguistically significant, it will not be shown. For example Estonian has palatalization in places similar to Livonian, but they are weaker, and so not explicitly indicated.

But there is more to the Venetic dots than simply the common palatalizations of consonants we know in modern languages. They appear to have a broader more general application than what is meant by the modern conventional idea of ‘palatalization’.

Dots around the Venetic N and L have easy comparison to modern Spanish or Livo-nian. And dots around Venetic D and T are analogous to those in Livonian. But there are other applications of dots in Venetic. After completing my project, it was very clear that the dots marked all situations in which the forward, upward, tongue modi-fied a letter sound from its normal relaxedtongue state. And that results in the dots marking consonants in other ways than what we might normally consider palatali-zation. We already saw how the dots modified vowels – introducing a J or H sound.

18

That too is not what we normally associate with the term ‘palatalization’. The scheme of dot addition in general makes things very easy. It is also the reason the dots were even used –it was a scheme that any writer could understand: For any tongue action up to to the top of the mouth, add a dot!!! Let us explore additional application on consonants: From all the evidence so far, if the dots in the Venetic writing surround a consonant like an “S” we should discover its sound very simply by adding our faint “J” (=”Y”), where the dot appears, and interpret the result. For example .s. sounding like “JS” can be considered the sound of the ss in English issue. In modern langu-ages this sound is represented in many ways, beginning with the “SH”, which is de-scribed in other languages with “Š” Currently a Venetic character that looks like an M is assumed to be “SH” but this dot scheme suggests the current view about the M is wrong and that the “SH”is the dotted S as in .s. What then should the M be? I will give the argument later, but for now I believe it to be an unpalatalized “(I)SS”as in English hiss. I therefore represent the character in the transcriptions to Roman alphabet with $.

The following table shows some palatalized consonants, and Venetic examples. In addition, I selected some Estonian words that are similar to the Venetic, where Esto-nian has palatalization in the same locations. Livonian will have similar examples. A more comprehensive study might also look for parallels in other palatalized langu-ages, like Danish. The reader is invited to investigate if these locations of palatali-zation are more or less universal, and a function of preceding and following sounds.

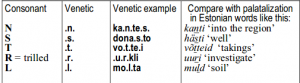

Table 3.5

PALATALIZATION OF CONSONANTS COMPARISON

Consonant

NS

T

R = trilled

L

Venetic

.n.

.s.

.t.

.r.

.l.

Venetic example

ka.n.te.s. = alueelle

dona.s.to = hyvin

vo.t.te.i = ottaa

.u.r.kli = tutkia

mo.l.ta = maa, multa

Compare with palatalization in Estonian words like this:

kanti ‘into the region’

hästi ‘well’

võtteid ‘takings’

uuri ‘investigate’

muld ‘soil’

The table shows another consonant that we would not normally consider a palata-lized consonsant. I propose dots around the Venetic R represent a trilled R. The R with dots does not appear often in Venetic, but there is an inscription in which a trilled and non-trilled R appear together – .a.tra.e.s. te.r.mon.io.s. The R in the first word, by out theory, is not trilled and in the second it is trilled. We can find that in lan-guages that have the trilled R, the trilling strength is also dependent on its situation within the word – the letters preceding and following. For example, Estonian uses trilling, and we can find that a word like adra produces the R in a weak position that does not have to be trilled, while on the other hand, tarvis places the R in a stronger position that promotes strong trilling. Estonian will, like Venetic, similarly strongly trill the loanword terminus (is it from Greek?) which is similar to the Venetic te.r.min.io.s.

I believe that for a person who already knew the language, the dots as represen-tations of all tongue-effects was enough for the reader to recognize what sound was intended. The dot was an all-purpose phonetic marker, but mostly marked palatalization and other tonguemodifications of pure sounds.

19

3.6 Dots in Venetic Around Silent Consonants Representing a Stød?

Let us consider now, what happens if we “palatalize” a silent consonant (if dots sur-round a silent consonant). That would be represented in Livonian explicitly with the D or T with the cedilla mark beneath it. But in Venetic we see it also around other si-lent consonants, such as G (.g.). How can silence be palatalized? The true palatali-zing of a silent consonant should result in more silence, and that would be represen-ted by the break in tone called “stød”. Represented by a mark similar to an apost-rophe, stød is found today in the highly palatalized langugages of Danish and Livo-nian.Stød can be viewed as palatalization on a high vowel so that the high vowel dis- appears from being ultra high. For example “I” >“J/Y”. Indeed the Venetic dotted “I” is an overhigh “I” that becomes silent while the tongue positions are the same as with “I”. Normally it appears as the “J/Y” or a frontal “H”. But what if we have “MIN”? Then raising the “I” in this case becomes “MJN” or “M’N”. This is in Danish called “stød”.

In Livonian an example of a word with stød would be jo’g ‘river’ where ’marks the stød. Estonian, without the stød would say it jõgi. Based on our view of the Venetic dots, if we used Venetic writing to write the Livonian it would probably look like jo.g. except that Venetic “j” would be written .i. (palatalized “I”) so it would be .i.o.g. or simply .o.g .

Another example in Livonian would be le’t ‘leaf’. If we wrote it in Venetic writing,by our theory, it would be le.t. In this case the Estonian equivalent without the stød would be leht and the Finnish would be lehti.

Another Livonian example would be tie’da ‘to do’. The Estonian equivalent would add the H

here as well – teha. In Finnish tehdä.

Perhaps one can find similar situations when comparing Danish words and equiva-lent words in related standard Swedish or Norwegian which are not highly palata-lized. It appears that palatalization arises from the general movement of a language upward towards tighter mouth and more involvement of the tongue on the palate.

The addition of the H by Estonian suggests the Livonian stød can be seen as an ‘extreme palatalization’. If a culture in general develops a dialect in which they push all vowels upward (which means pushing vowels forward-upward while relaxing the mouth) then we get a general shift that can roughly be described by U>O O>A A>E E>I But what about the I? What is higher than the I ? Obviously it is the “J/Y”or fron-tal “H”. But then what happens with the “H” or “J/Y”? That is when the stød appears. Already silent, where can it go? The only direction it has would be to create a break, a stop. Thus, to continue the shift we would have I > H (tongue in “J” position) and then H,J > stød. If we start with a word like SOMAN it can evolve as the speaker’s tongue grows. Follow the rise in vowels: SOMAN > SAMEN >SEMIN > SIMHN> SIM’N

Thus in general palatalization and upward shifts of vowels are related to the same shift in speech. It follows that highly palatalized languages also display upward shifts of lower vowels too. For example Livonian presents the suffix for agency as – ji while Estonian and Finnish use – ja.It may explain the name Roman historian Tacitus used for the nations along the southeast Baltic coast in the first century – “Aestii”. If these people were ancient Estonians, and the reason Estonians have always been called Eesti, then maybe if the word was highly palatalized, we could rewrite it (imitating Li-vonian) as ESTJI, which when lowered becomes OSTJA of low palatalized Estonian and Finnish, which means ‘buyer’, ie ‘merchant’, which is how surrounding peoples would have viewed the managers of the market port near the Vistula mouth.

20

It is never a uniform shift because many other factors are at play as well. A speaker cannot change a word so much it becomes unintelligible. Some crutial features, such as grammatical endings, may resist being changed. The changes will mostly manifest in the word stems.

In Venetic, in the available Venetic inscriptions, this shifting of vowels upward de-scribed above, can explain words in which no vowels are shown between conso-nants where one would expect it. In the body of inscriptions we see vda.n. and mno.s. If the above is true of Venetic then we can expect that earlier vda.n. may have been vhda.n. or v.i.dan and before that vida.n. Similarly mno.s. may originated from m.n.os and before that mino.s. In other words the progressions are v.i.dan > v.d.a.n. > vda.n. and mino.s. > m.n.o.s. > mno.s.

We have possible proof of this in the Venetic inscriptions, where a word written se-veral times as vo.l.tiiomno.i. appears in another dialect . vo.l.tiio.m.minna.i. thus re-vealing the original “I” between M and N.(One of the advantages of Venetic writing is that the scribe actually records actual dialect and in this case,a less palatalized one!) The occurrence of two vowels together as in vda.n. or mno.s. was rare in Venetic as these are the only two occurrences in the body of under 100 complete inscriptions available.

3.7 Solitary Dots

Sometimes dots appeared only once, not around a letter. Solitary dots probably are to be interpreted in the following manner: After a silent consonant they could pro-duce a pause. After a vowel they could lengthen the vowel. We have to use common sense and put ourselves into the mind of the scribe. The writing system has no other way of indicating length or pause.

Sometimes scribes treated each palatalized character with a dot on either side, but if there were two palatalized characterized in a row, often the dot between them was shared.In our arbitrary division of the continuous Venetic writing with spaces to show word boundaries, a shared dot can become separated from one of the adjacent cha-racters using it. Bear this in mind when I break up a continuous Venetic inscription with word boundaries to make our analysis simpler.

4. ANCIENT PHONETIC CONNECTIONS? VENETIC AND DANISH

4.1 Venetic at the South End of the Jutland Amber Route Implications on Danish All in all, from the use of the phonetics of regular words (which we assume were pro-nounced like Latin) plus the additional effects indicated by the dots, we can sense how the Venetic actually sounded –strongly palatalized.

As already mentioned, two languages with strong palatalization and stød is Danish and Livonian. Livonian lies south of Estonia and was dominated by Latvian (an Indo-European language that is a cousin of Slavic languages) and therefore we might propose that Livonian palatalization arose from the influence of Latvian. Another possibility is that Livonian was actually strongly influenced by traders from the west Baltic who spoke in a palatalized way who regularly accessed the trade river known in Livonian as Vaina, but today as Daugava.

But let us look at Danish, because Danish is today spoken by descendants of peoples who lay at the north end of the trade route that reached down to northern Italy where the Venetic inscriptions we are studying have been found. Both ancient historical texts and archeology has demonstrated that the Veneti were agents of amber from the north.

There were two northern sources of amber –the southeast Baltic, and the Jutland Peninsula.

Most of the amber to the Venetic regions at the north end of the Adriatic Sea came from the Jutland Peninsula. The amber from the other source, the southeast Baltic, coming down via the Vistula and Oder, went mostly directly to Greece. With the rise of the Romans, there appears to have been a detour of the Vistula trade path west-ward however, coming down the Piave River Valley. But inscriptions from the Piave Valley and eastward are few,and the body of Venetic inscriptions that archeology has uncovered, mainly represents language of the peoples who recieved amber from the Jutland Peninsula route. Most of the inscriptions, thus, have the high palatalized dia-lect, and it is likely it was also found at the Jutland Peninsula source of amber, which we can perhaps identify with the language of independent peoples Roman identified as “Suebi” who we will here say spoke “Suebic”

As we have already noted archeology is clear about the intimate connection between the Adriatic Veneti in the region of most of the inscriptions, and the Jutland Peninsula. According to Grahame Clark (World Prehistory, Cambridge Univ Press) based on the archeological data, the early amber route went up the Elbe, then made its way south by using both the Saale and upper Elbe to start. But then, … in the se-cond phase of the central European Bronze Age, a distinctive bronze industry, asso-ciated with tumulus burial, arose among descendants of Corded-ware folk [Indo-Eu-ropeans ancestral to the Celts or Germans] occupying the highlands of south-west Germany… These are identifiable in my view with the true Germans – those Tacitus (see his Germania of 98AD) calls Chatti. They were sedentary farming and pastoral peoples and hence customers for traders.

Thus their growth caused the traders from Jutland to develop in their route an additional westward detour or loop to that area.

Then, after that, another center of industry developed east of the Saale River by people of the same Corded-ware origins (Germanic). The growth of the Germanic culture in central Germany is evident, which in turn promoted traders to create mar-kets for them. The impact of this on the traders is that the trader colonies at the ter-minuses in northern Italy and the Jutland Peninsula developed as well. As Clarke in-dicates: Another distinctive industry developed in Northern Italy adjacent to the south end of the overland route,and at its northern end the Danes …were importing bronze manufactures both from central and also from western Europe This information affirms the connection between activity in northern Italy and Jutland Peninsula. The “Danes”were recieving bronze wares in exchange for their supplying amber to the southern civilizations. The ”Danes” at this time were not Germanic. In general, The amber route formed a veritable hub around which the Early Bronze Age industry of much of Europe revolved.

It is thus clear that the Danes of ancient times spoke another language,one that may even have been analogous to Venetic, and there is a distinct possibility that their tra-der peoples were the initiator of Venetic colonies to serve a newly opened up way around 1000BC of carrying Jutland amber south to Mediterranean civilization. Then when the Jutland tribes were conquered by the German-speaking Goths (Chatti, Gö-ta) since Roman times, some centuries later,they adopted the Germanic language of their conquerors, but spoke it in their original highly palatalized fashion. A new lan- guage is initially always spoken in the accent of the old. If one does not experience an environment of ‘correct’ speakers, one will continue to speak it with the accent, and transfer the accent to subsequent generations. Danish can be seen that way – as an accent originating from Suebic of the Roman era, carried down through the generations. Southern Sweden (Skåne) has a highly palatalized dialect as well, and it indicates that the palatalized Suebic language was found also in southern Sweden.

22

Little is known about the Suebic language other than from what is implied in ancient writings. According to Tacitus’ Germania, it seems the Suebic language covered vast part of the geographical region of Germania, like a trade language. Some have been tempted to see it as some early form of Germanic, but we cannot forget that the re-gion the Romans called “Germania” was purely a geographic region, and could have contained many languages and dialects.