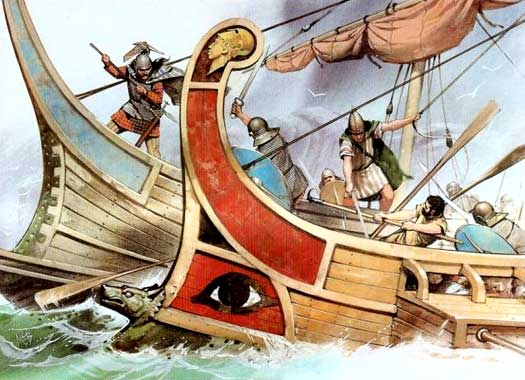

Oheisessa kuvassa etualalla olevan roomalaisen kaleerilaivan kannelta roomalai- set sotilaat, jotka on tunnistettavissa jumalattoman suuresta jalkaväen kilvestä, ja vähemmän suojavarustettu kelttiläinen seppämestari liittolaisheimosta itse teke- mänsä erikoisen pitkävartisen teräaseen kanssa hyökkäävät taaempana olevan komeamman veneettiläisen kauppa- ja sotapurjelaivan kimppuun, joka luultavasti seisoo rasvatyynessä, eikä siinä ole airoja eikä soutajia. Sitä piirittää luultavasti kaksi muuakin kaleeria, joita purjehtijalle ”huono” ilma ei lainkaan haittaa, päin vastoin. Paikka on Britannian kanaali ja vuosi on 56 e.a.a.eli noin 100 vuotta myö- hemmin kuin Adrianmeren veneetit olivat varmistaneet Roomalle voiton 2. puu- nilaissodassa ja supervalta-aseman Välimerellä. Myös nämä Breagnen veneetit, jotka kuljettivat pronssiin tarvittavaa tinaa Britanniassa manner-Eurooppaan, olivat olleet Rooman ylimpiä ystäviä aina siihen asti, kun vuonna 58 e.a.a. Gallia Transalpinan maaherraksi nimitettiin Julius Caesar, joka muuten johti itsekin sukujuurensa peräti veneettien Venus-jumalattaresta. Hänen mielestään veneetit hallitsivat liian kriittisiä resursseja Rooman kannalta.Rannikon naapurikansat lisäksi seurasiva poliiisesti heitä eivätkä Roomaa. Rooman laivastoa komensi muuan (Marcus Junius) Brutus, joka tässä yhteydessä saavutti Caesarin jakamattoman (joskin tunnetusti katteettoman) luottamuksen.

Näin kertoo Caesar itse:

Gallian sota:

II 34

” … At the same season Publius Crassus whom he [Caesar] despatched with one legion agaist the Veneti, Venelli, Osismi, Curiolotae, Esubii, Aulerci and Redones, the maritime states which border upon the ocean, reported that all those states had been brought into subjection to the power of Rome. … ”

III 7

” … But at this point the war broke suddenly in Gaul, of which the cause was as follows. Publius Crassus the younger (Jr.) with Seventh legion had been wintering at the by the Ocean at the Andes. As there was a lack of corn in those parts, he despatched several commandants and tribunes into the neighbouring states to seek it. Of these officers Titus Terrasidius was sent to the Esubii, Marcus Trebius Gallus among the Curiosolites, Quintus Velantius with Titus Silius among the Veneti.

Thsese Veneti exrcise by far the most extensive authority over all the sea cost in these districts, for they have numerous ships, in which it was their custom to sail to Britain and they excel the rest of the theory and practice of navigation. As the sea is very boisterous, and open, with a few harbours here and there which tehy hold them- selves, they have as tributaries almost all those whose custom is to sail that sea. It was Veneti who took the first step,by detaining Silius an Velanius supposing that through them they should recover their own hostages whom they had given to Crassus. Their authority induced their neighbours – for the Gauls are sudden and spasmodic in their designs – to detain Trebius and Terrasidius or the same reason, and, rapidly despatcing deputies among their chiefs,they bound themselves by mutual oath to do nothing save by common conscent, and to abide together the single issue of their destiny. Moreover, they urged the remaining states to choose rather to abide in the liberty received from their ancestors than to endure Roman slavery. The whole sea-cost was rapidly won to their opinion, and they dispatched a deputation in common to Publius Crassius, bidding him restore their hostages if he would receive back his own officers.

Caesar was informed by Crassus concerning these matters, and, as he himself was at some distance, he ordered men-of-war to be built meanwhile on the the river Loire , which flows into Ocean, rowers to be drafted from Provence, see- men and steersmen to be got together. These requirements were very rapidly executed, and so soon as the season allowed he himself hastened to join the army.

The Veneti and likewise the rest ofthe states were informed of Caesar´s coming, and at the same time they perceived the magnitude of their offence – they had detained and cast into prison deputies, men whose title had ever been sacred and inviolable among all nations . Therefore, as the danger was great, they began to prepare for war on a corresponding scale, and especially to provide naval equipment, and the more hopefully because they relied much on the nature of the country. They knew that on the land the roads were intersected by estuaries, that our navigation was hampered by ignorance of the locality and by the scarcity of harbours, and they trusted trusted that the Roman armies would be unable to remain long in their neighbourhood by the reason of lack of corn. Moreover, they felt that, even though everything should turn out contrary to expectations, they were predominant in sea power, while the Romans had no supply of ships, no knowledge of the shoals,harbours, or islands in the region where they were about to wage war, and they [Veneti] could see that navigation on a land-locked see was quite different from navigation on an Ocean very vast and open. Therefore, having adopted this plan, they fortified their towns, gathered corn thither from the fields, and assembled as many ships as possible in the campaign. As allies for the war they took to themselves the Osismi, the Lexovii, the Namnetes, the Ambiliati, the Morini, the Diablintes, and the Menapii; and they send to fetch auxiliaries rom Britain, which opposite those regions.

The difficulties of the campaign were such as we have shown above; but, never- theless, many considerations moved Caesar to take it. Such were the outrageous detention of Roman knights, the renewal of war after surrender, the revolt after hostages given, the conspiracy of so many states – and, above all, the fear that if this district were not dealt with the other nations might suppose they had the same liberty. He knew well enough that almost all the Gauls were bent on revolution, and could be recklessly and rapily aroused to war; he knew also that all men are narurally bent to liberty, and hate the state of slavery. And thereore he deemed it proper to divide his army and disperse it at wider intervals before more states could join the conspiracy.

According to the dispatched Titus Labienus, lieutent-general, with the cavalry to the territory of the Treveri, who live next the river Rhine. His instructions were to visit Remi and the rest of the Belgae, and to keep them loyal, and to hold back the Germans, who were said to have been summoned by the Belgae to their assistance,in case they should endeavour to force the passage of the river by boats. Publius Crassus, with twelwe cohorts from the legions and a large detach- ment of cavalry, was ordered to start for Aquitania to prevent the dispatch of auxiliaries from the tribes there into Gaul, and the junction of the two great nations. Quintus Titurius Sabinus, lieutenant-general, was depatched with three legions to the territory of Venelli, the Curiosolites and the Lexovii, to keep that force away from the rest. Decimus Brutus the younger was put in command of the fleet, and the Gallic ships already ordered to assemblerom the territory of Pietones, the santoni and others now pacified, and was ordered to tart as soon as possible for the country ofthe Veneti, whither caesar himself hastetened with the land force.

…

III 13

… Not so the ships of ”Gauls” [Veneti],for they were built and equipped in the fol- lowing fashion. Their keels were considerably more flat than of our own ships, that they they might more easily weather shoals and ebb-tide. Their prows were very lofty, and their sterns were similarly adapted to meet the force of waves and storms. The ships were made entirely of oak, to endure any violence and buffeting. The cross-pieaces were beams a foot thick, fastened with iron nails as thick as a thumb. The anchors were attached by iron chains intead of cables. Skins of peaces of leather fine finished were used instead of sails, either because the natives had no supply of flax and no knowledge of its use, or, more propably, because they thought that the mighty ocean storms and hurricanes could not be ridden out nor the mighty burden of their ships conveniently controlled, by means of sails. When our own fleet encountered these ships it proved its superiority only in speed and and oarsmanship; in all other respects, having regard to the locality of the tempests the others were more suitable and adaptable. For our ships could not them with ram (they were stoutly built), nor by reason of their height, they were, was it easy to hurl a pike, and for the same reason they were less rapidly gripped with grapnels. Moreover, when the wind began to rage and they ran before it, they endured the storm more easily, and rested in shoals more saely, with no fear of rocks or crags if let by the tide; whereas our own vessels could not but dread the possibility of all these changes.

II 14

Caesar had taken several towns by assault , when he perceived that all his labour availed nothing, since the flight of the enemy could not be checked the capture of towns, nor damage done to them; accordingly he determined to aweit the fleet. It assembled in due course, and so soon as it was sighted by the enemy about two hundred and twenty of ships, fully prepared and provided with every kind of equip- ment, sailed out of harbour and took station opposite ours. Brutus, who commanded the fleet, and his tribunes and centurios in charge of single ships, were by no means certain what to do or what plan of battle they would pursue, or our commander knew the enemy could not be damaged by the ram; while, even when turrets were set up on board, the lofty sterns of the native ships commanded even these, so that from the lower level missiles could not be hurled property, while those discharged by the Gauls gained heavier impact. One device our men had prepared to great advantage – sharp-pointed hooks let and in and fastened to long poles, in shape not unlike siege-hooks. When by these contrivances the halyards which fastened the yards to the masts were caught and drawn taut, the ship was rowed hard ahead and they were snapped short. With the halyards cut the yards of necessity fell down; and as all the hope of the Gallic ships lay in their sails and tackle, when those were torn away all change of using their ships was taken away also. The rest of the conflict was a question of courage, in which our own troops easily had the advantage – the more so because the engagement took place in sight of Caesar and of the whole army, so that no exploit a little more gallant than the the rest could escape notice.The army, in fact, was occupying all the hills and higher ground from which there was a near view down upon the sea.

III 15

When the yards had been torn down as described, and each ship was surraoun- ded by two or three, the troops strove with the utmost force to climb on the enemies ships. When several of them had been boarded, the natives saw what was toward; and, s they could think of no device to meet it, they hastened to seek safety in flight. … ”

Rooma joutui valtaamaan Britannian veneettien takia, vaikka valtakunnan hallit- sematon laajeneminen oli tunnustettu ongelma – eikä varsinaisesti ”Korkein Täyttymys” sellaisenaan.

Kyseinen työkalu oli tarkoitettu purjelaivojen hamppuköysien katkomiseen, jonka jälkeen ainakin veneettinen silloiset laivat olivat ohjauskelvottomia. Oli selvää, että sille löytyy aika pian vastaveto. Liikkuvat veneetit liittoutuivat germaanien kanssa, jotka oliva aina olleet Rooman vihollisia.

Rooman oli otettava haltuunsa tinan lähteet ja tuotanto. Koko pronssikausi oli kuitenkin pian fööbii.

PS: Toisin kuin roomalaiset, veneetit ja gemaanit, jotka luottivat yli kaiken suojau-tumiseen, kelttiläiset soturit luottiva hyviin keveisiin aseisiin, suureen liikkuvuueen (mukaan lukien liukas pako) ja sulautumiseen maastoon ja väestön joukkoon (mikä edellytti sen kannausta).

Kuvassa Insubrien kelttiheimon päällikkö Ducarius, sillä kertaa Hannibalin liitto- lainen, listii roomalaisen (tyhmän) komentajan konsuli Gaius Flaminiuksen Trasi- mene-järven taistelussa vuonna 17 e.a.a. Tämä oli myös kosto siitä, että Rooman konsuli Marcus Claudius Marcellus (joka oli nyt reservissä Rooman kaupungin preetorina) listinyt kaksintaistelussa heimon ja koko Gallian entisen komentajan Viridomaruksen, kun roomalaiset olivat vallanneet heidän pääkaupunkinsa Mediolanumin (Milanon).

Onko historiasta löydetty uusi suomalais-ugrilainen kieli?

Suomen sana viikate , viron vikat, tulee Baltian veneettien naapureiden kuurilaisten kielestä baltologi Eino Niemisen mukaan.

http://kaino.kotus.fi/algu/index.php?t=sanue&sanue_id=121602

| viikate |

”The explanation is phonologically very problematic, but perhaps not totally impossible.” |

|

| Junttila, S. 2012 SUST 266 s. 273 |

http://eki.ee/dict/ety/index.cgi?Q=vikat&F=M&C06=et

vikat : vikati : vikatit ’pika varrega riist heina ja vilja niitmiseks’

? ← balti *vikapteš

läti izkapts ’vikat’

● liivi vikārt ’vikat’

vadja vikahtõ, vikastõ ’vikat’

soome viikate ’vikat’

isuri viigade ’vikat’

Aunuse karjala viikateh ’kõver rauts’

lüüdi vikateh ’vikat’

vepsa vitakeh ’vikat’

Vt ka viker-1.

Tämä lainaus on Fraenkelin Liettuan etymologisesta sanakirjasta:

https://hameemmias.vuodatus.net/lue/2015/10/suomen-sanat-fraenkelin-liettuan-etymologisessa-sanakirjassa

Lithuanian: kapóti (kapója, kapójo) = hakata (mäsäksi), halkoa, otella

Etymology: ’hacken = hakata, spalten = halkaista, lohkoa, (zer)schlagen = lyödä kappaleiksi, hauen = hakata,tapella,prügeln = piiskata, Schnabelhiebe versetzen = nokitella, niedermachen = alistaa, töten = tappaa’,

kapótis ’scharmützeln’ = otella,

kapõklė ’Hackbrett = koverruspölkky, Axt zum Aushöhlen einer Mulde, eines Troges’ = kuokkakirves ruuhen kovertamiseksi,

kapõklis ’Schlichtbeil’ = piilukirves (hirsien veistämiseen), ”tasokirves”

kapõtė ’Hackbrett’ = koverruspölkky (Skardžius ŽD 352),

kaplỹs (kãplis) = kaplễ ’Haue = kuokka, Spitzhacke = hakku, Karst = kuokka, Schlichtbeil = piilukirves’ und ’stumpfe Axt = lyhyt kirves, stumpfes Beil = lyhyt(teräinen) piilu, Schneidezahn = laikkaukärki, Dummkopf = pölkkypää, Tölpel = typerys’,

kapõčius = kaplễ

kap(š)nóti, kapsė’ti ’langsam picken’ = nokkia,

kapõjė ’Zeit des Holzspaltens = puunpilkonta(-aika)’, kapõnė (s.s.v.),

kopìkai ’Spechte’ (eig. ’Hacker’) = tikka,

lett. kapāt ’hacken = hakata, (klein) hauen = kuokkia, schlagen = lyödä, stampfen = tampata, zernagen = hajottaa, fressen = hyödä, hotkia (eläin. eläimellisesti)’,

kapeklis ’Hackeisen’ = tarttumarauta,

kaplis ’Hacke, Hohlaxt’ = hakku, putkikirves

kapēt ’mit dem kaplis (den Boden) auflockern, scharren, umwenden’ = naarata,

kaplēt, -īt ’mit der Hacke die Erde um die Kartoffelstaude ziehen, hacken’ = perunakuokka,

izkapts, –pte (= ”poislyönti”) ’Sense’ = viikate

(daraus finn. viikate, Gdf. *vikapteš, Nieminen LPosn. 5,79 ff.), (”Viikate” lienee ollut kuuriksi ”vikaptes”, ”kaikenleikkaava”, ”poisleikkaava”, mutta tuo vi- tuossa merkityksessä ”pois” on slaavia, ilmeisesti puolaa; tai sitten se on ”kaikenleikkaava”.).

lit. kàpti (kàpia, kàpė) (1. kapiù) ’hauen = kuokkia, hakata, tapella, fällen’,

kàpti (kãmpa, kápo) (1. kampù, kapaũ) ’zerschlagen werden = hajota, erota (geom.: kãmpas = kulma), müde werden = väsyä’

(cf. zur Bed. griech. kòptein ’sehlagen, stossen = törmätä’ und ’ermüden = väsyä’,

kòpoj ’Schlag = isku’ und ’Ermüdung = väsymys, Ermattung = uupumus, Entkräftung = voimattomuus’

Kommentti: Tämän lähteen ”kreikka-etymologiat” ovat samaa sarjaa kuin Koivu- lehdon ”vanhat kermaanietymologiat”: kreikan ”-o-” EI MUUTU baltin –am-:ksi lainattaessa, ei sitten ei niin millään… Päinvastoin kyllä voi tapahtua, mutta siitäkään tuskin on kyse, niin tiiviissä vuorovaikutuksessa kuin preussilaiset galindit/skalvit ja kreikkalaiset aika ajoin olivatkin, koska baltit toimittivat antiikin kreikkalaisten himoitsemaa meripihkaa);

preuss. enkopts ’begraben’ = haudattu, upotettu, ympätty

… ”

Ruohoviikate on saattanut hvinkin läheä kehittmään aseviikatteesta. Sirppi on kuitenkin tunnettu tuhansia vuosia aikaisemmin.