https://www.theguardian.com/world/shortcuts/2013/sep/01/winston-churchill-shocking-use-chemical-weapons

Winston Churchill’s shocking use of chemical weapons

Secrecy was paramount. Britain’s imperial general staff knew there would be outrage if it became known that the government was inten- ding to use its secret stockpile of chemical weapons. But Winston Churchill, then secretary of state for war, brushed aside their concerns. As a long-term advocate of chemical warfare, he was determined to use them against the Russian Bolsheviks. In the summer of 1919, 94 years before the devastating strike in Syria, Churchill planned and executed a sustained chemical attack on northern Russia.

The British were no strangers to the use of chemical weapons. During the third battle of Gaza in 1917, General Edmund Allenby had fired 10,000 cans of asphyxiating gas at enemy positions, to limited effect. But in the final months of the first world war, scientists at the govern- mental laboratories at Porton in Wiltshire developed a far more devas- tating weapon: the top secret ”M Device”, an exploding shell contai- ning a highly toxic gas called diphenylaminechloroarsine. The man in charge of developing it, Major General Charles Foulkes, called it ”the most effective chemical weapon ever devised”.

Trials at Porton suggested that it was indeed a terrible new weapon. Un-controllable vomiting, coughing up blood and instant, crippling fatigue were the most common reactions. The overall head of chemical warfare production, Sir Keith Price, was convinced its use would lead to the rapid collapse of the Bolshevik regime. ”If you got home only once with the gas you would find no more Bolshies this side of Vologda.”The cabinet was hostile to the use of such weapons, much to Churchill’s irri- tation. He also wanted to use M Devices against the rebellious tribes of northern India. ”I am strongly in favour of using poisoned gas against uncivilised tribes,” he declared in one secret memorandum. He criti- cised his colleagues for their ”squeamishness”, declaring that ”the ob- jections of the India Office to the use of gas against natives are un- reasonable. Gas is a more merciful weapon than [the] high explosive shell, and compels an enemy to accept a decision with less loss of life than any other agency of war.”

He ended his memo on a note of ill-placed black humour: ”Why is it not fair for a British artilleryman to fire a shell which makes the said native sneeze?” he asked. ”It is really too silly.”

A staggering 50,000 M Devices were shipped to Russia: British aerial attacks using them began on 27 August 1919, targeting the village of Emtsa, 120 miles south of Archangel. Bolshevik soldiers were seen fleeing in panic as the green chemical gas drifted towards them. Those caught in the cloud vomited blood, then collapsed unconscious.

The attacks continued throughout September on many Bolshevik-held villages: Chunova, Vikhtova, Pocha, Chorga, Tavoigor and Zapolki. But the weapons proved less effective than Churchill had hoped, partly because of the damp autumn weather. By September, the attacks were halted then stopped. Two weeks later the remaining weapons were dumped in the White Sea. They remain on the seabed to this day in 40 fathoms of water. ”

https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/gallipoli-was-not-churchills-great-folly-20110413-1ddzb.html

Henry Alfred Hillman – RFC-RAF Cook & Aircraft Mechanic with the North Russia Expeditionary Force in 1919

Henry Alfred Hillman survived World War One. Those who died gave their lives.

Many of those who lived through it all gave the rest of their lives as the result of their horrific experiences!

My Great Uncle – Henry Alfred Hillman – was to me as a child, a myste- rious person whom I never met – he died two years before I was born. I learned about him from my father, who described how his war service had unsettled him, and he was never “quite right” afterwards. My father could only tell me that he had fought in the First World War, that he had been gassed, and that he had served in Russia, and had never really recovered from his experiences.

Many years later I began to do research on Great Uncle Henry – fondly known to my father as “Uncle Alfie” from his second name. I quickly came up against a brick wall with the attempt to acquire his service record from the Historical Disclosures Section of the Army Personnel Centre. I even had his Service Number, or so I thought, from a photo card of which I have copies, that he sent to a number of relatives. The response came back that there was no trace found for the name or number, and thus his record must be one of those lost to fire during the Second World War. I also learned later that Service Numbers were not necessarily with a man throughout the War, but could be changed on transfers.

So there he remained – a mystery – until I happened to mention him to a person we met in Australia. She put the query out over the wires, and by the next morning he had been found – in the Royal Flying Corps – not in the Army at all. His Service Record was quickly found and provided the basis for further research.

Henry’s Service Record indicates that he was with the North Russia Ex-peditionary Force between the dates of 4th July 1919 and 14th Septem- ber 1919. This is a period of a little over two months – or 73 days to be exact. It is not clear from the record whether the dates are inclusive of the period in Russia, or include periods during which he was travelling there and back – most likely by sea. There is a gap of six weeks between his record at RAF Halton (19th May 1919) and his transfer to the North Russian Expeditionary Force (4th July 1919). He was “dispersed” from RAF Blandford to RAF Halton only a month after his time with the NREF ended on 13th October 1919 where his Service Record ends.

No information has been found as to where he was based while in Russia, nor how he was involved, other than that he was a “cook”. His promotion record indicates that by January 1918 he was an Air Mechanic, 3rd Class with the RFC, and shortly afterwards on 1st April 1918 a Private, 2nd Class.

Henry joined up late in the War in mid 1917. He recorded his Will, and wrote a letter to his parents and siblings the day before he joined up on 18th June 1917. He was just 23 years old. We do not know why he waited so long before enlisting. It is evident he saw his duty as being to England, and not any King nor Government. His thoughts prior to departing are recorded in the letter to his parents, reproduced as an annex below. In 1918 he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, which evolved into the Royal Air Force by April of the same year.

Apart from the dates on his Service Record of his time in Russia, it has not been possible to obtain any further information on what he actually did or where he travelled in North Russia. However, reading between the lines in his letters to his brother (my Grandfather) later in life, and background reading on the later stages of the War in Russia, a likely scenario emerges.

He clearly suffered from his experiences, and this remained with him for the rest of his life,to his death from emphysema and heart degeneration in 1946, aged only 52. This is further borne out by the letters he sent to his brother, while he – Henry – travelled to Australia for a year in 1933 “to get away from it all”. The letters contain the phrases –

- “Giving his nerves a rest”

- “get rested a bit more”

- “get over my trouble”

- “can’t break that mental connection off here”

- “They know about it here and it comes from all over Western Australia and still comes from England”

- “I cannot break off that telepathic connection”

This was 13 years after the events of the Great War, giving some indication of its longterm effects upon him. He died in 1946, another 13 years after his Australian trip, and 26 years after his experiences in Russia. While he makes no actual mention of his time in the Great War, all the information we have from this man’s life points to traumatic experiences at that time.

So what on earth happened that he felt like this, and how did he come to suffer from a gas attack, sometime after gas had last been used, and then on the Western Front where he did not serve?

We have found no direct evidence, but there are a number of events during the very brief North Russia Expeditionary Force existence that may well indicate what these experiences were.

Ira Jones in his 1938 book “An Air Fighter’s Scrapbook” recounts how they travelled by ship from Leith in Scotland, arriving at Archangel (Archangelsk) in Russia in June and leaving again in September 1919. This was a volunteer RAF unit, known locally as No.3 Squadron under Geoffrey “Beery” Bowman. This period almost exactly coincides with Henry’s Service Record NREF period (4th July – 14th September 1919). Ira Jones reports are all from the Archangel and Bereznik airfield area with no mention of the use of gas, apart from one brief aside. He mentions a colleague (Roddy Waugh) involved in August with gas bombing from the air at Pinega – east of Archangel and Beresnik.

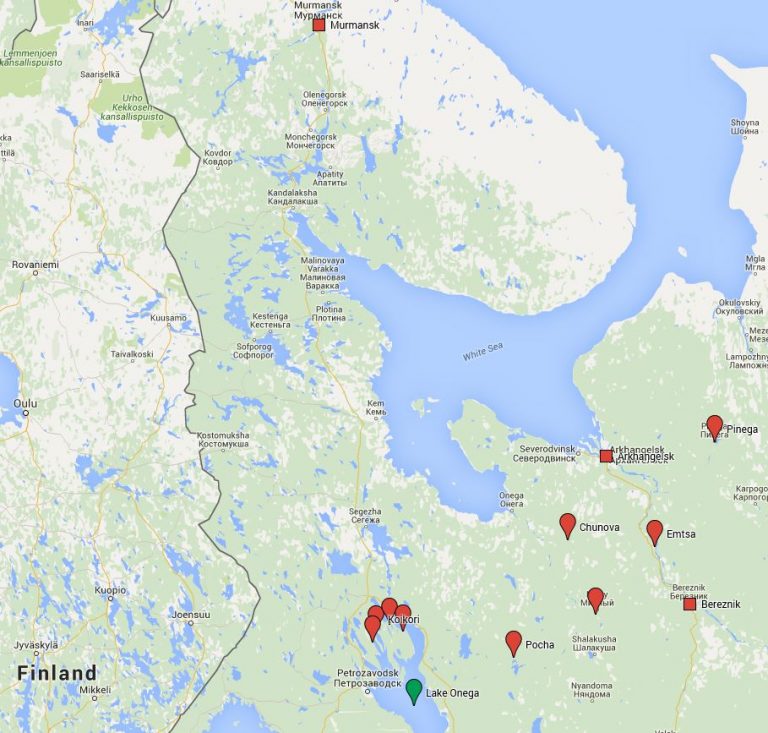

Simon Jones (1999) however, records the use of “M bombs” delivered from the air by the Archangel and presumably Beresnik based RAF between 27th August and 4th September 1919 on the villages of Emtsa Station, Chunova, Plesetskaya Station, Vikhtova and Pocha. Soon afterwards (12-22 September 1919) they were dropped from the air by Murmansk based RAF aircraft on the villages of Kavgora, the Chorga line, Lijma, Mikheeba Selga, Tavoigor(a), Zapolki and Koikori on the Shunga Peninsula of Lake Onega. Following this, all M devices were in theory dumped in the White Sea as the British withdrew, although some evidence suggests the Russians were provided with a number (Jones 1999).

A map showing those locations bombed with M gas bombs has been compiled. The airline distance from Murmansk to the Shunga Peninsula in Lake Onega is 700 km. This seems an unlikely distance for a WWI aircraft – 1,400 km return flight? Bereznik was 800 km return from Shunga, and only 480 km to Pocha for example. Archangel to Pinega was only 300 km return.

[Yllä]

Did Henry become mixed up with these gas experiments and attacks – was he an Air Mechanic working on one of the airfields involved – Murmansk, Archangel or Beresnik?

Ira Jones also makes mention of the military executions carried out on soldiers that mutinied in the local area – both British and Russian – and clearly found it a harrowing experience himself. These mutinies are apparent from other accounts from this period –

- John Kelly, an Australian, recalled the campaign as one of “failures, treachery, hardship, mutiny and dangerous experiments” (Millar 2015).

- Millar (2015) also mentions a number of mutinies amongst the forces involved.

Mention is made in the Great War Forum of No.1, 2 and 3 Slavo-British Squadrons, or Slavo-British Air Corps (SBAC) serving in North Russia.

Peter Cooksley in his 2013 book “RFC Handbook 1914-1918” mentions the NREF assisting two White Russian forces – “Eklope” (or Elope?) at Archangel and “Syren” further north at Murmansk.

The picture becomes much grimmer reading through Simon Jones 2015 account of the experimentation with a new gas warfare system in North Russia – the “M Device”.This was a means of delivering “diphenyl- aminechloroarsine” as a fine dust. Its effects seem not to have been fa- tal, instead causing great discomfort that prevented normal activities for a time. The M bombs were dropped from the air on a number of vil- lages in order to halt the advance of the Bolshevik forces. Some British personnel exposed to the gas suffered from longterm debilitation – pains in the legs, head and back, extreme debility, anaemia and diar- rhoea, lassitude, fatigue, some paralysis, giddiness and breaking out in cold sweats some months later. One Australian sufferer who appeared five months later in front of a medical board in England was found to be “pale, nervous, and suffering from various phobias”, too afraid to return to Australia by ship.

The use of the weapon ended once it was found to require very specific conditions of wind and rain, and with the sudden retreat from North Russia in October 1919. The 47,000 unused devices were dumped in the sea (Jones 1999).

While only circumstantial, it would seem very likely that Henry too, somehow in his humble occupation as a cook and/or aircraft mechanic, was also exposed to the gas, and possibly the horrors of mutiny and subsequent public executions. We have no hard evidence, but these would certainly have been attenuating circumstances for what we would probably today call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) – a syndrome that even today military personnel can suffer from for years after being involved in warfare of any kind.

The villages mentioned as having been subjected to these gas attacks in North Russia have been mapped and may give some idea of where Henry was located during his North Russia service. Archangel or Mur- mansk areas would seem the most likely, given the lack of any mention of using gas bombs by Ira Jones, based at Beresnik. However, many of the sites where M gas was used must have been reached most efficiently by air from Bereznik? Perhaps the lack of mention in Jones account relates to an attempt to keep this use of gas as little advertised as possible.

Australians were clearly very involved in the NREF, so it is of interest that this is where Henry went some years later to try to “get over his troubles”. He also may have come across other Australians when in training in Britain before going to Russia since there were many Australians in training at RAF Blandford. It is evident from his photo albums of his Australia trip that he knew people already there.

We may never find further details of my Great Uncle’s service in and after World War One. While he served for only a short period, and never on the front line in mainland Europe in the famous theatres of war, but in the little-known aftermath – the ill-timed attempt to intervene in Russia ended with an ignominious withdrawal, with the loss of much equipment and armament.

Churcill aloitti Englannissa myös atoimipommin kehityksen, tosinsamaan aikaan ja vähän ennekin (1938) tekin myös Robert Oppenheimer USA:ssa. NL oli koko ajan selviollä molemmista hankkeista.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tube_Alloys

” Tube Alloys

Tube Alloys was a codename of the clandestine research and development programme, authorised by the United Kingdom, with participation from Canada, to develop nuclear weapons during the Second World War. Starting before the Manhattan Project in the United States, the British efforts were kept classified and as such had to be referred to by code even within the highest circles of government.

The possibility of nuclear weapons was acknowledged early in the war. At the University of Birmingham, Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch co-wrote a memorandum explaining that a small mass of pure uranium-235 could be used to produce a chain reaction in a bomb with the power of thousands of tons of TNT. This led to the formation of the MAUD Committee, which called for an all-out effort to develop nuclear weapons. Wallace Akers, who oversaw the project, chose the deliberately misleading name ”Tube Alloys”. His Tube Alloys Directorate was part of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.

The Tube Alloys programme in Britain and Canada was the first nuclear weapons project. Due to the high costs, and the fact that Britain was fighting a war within bombing range of its enemies, Tube Alloys was ultimately subsumed into the Manhattan Project. Despite reaching an agreement with the United States to share nuclear weapons technology, and to refrain from using it against each other, or against other countries without mutual consent, the United States failed to provide complete details of the results of the Manhattan Project to the United Kingdom. The Soviet Union gained valuable information through its atomic spies, who had infiltrated both the British and American projects.

… Origins

Discovery of fission

The neutron was discovered by James Chadwick at the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge in February 1932.[1][2] In April 1932, his Cavendish colleagues John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton split lithium atoms with accelerated protons.[3][4][5] Enrico Fermi and his team in Rome conducted experiments involving the bombardment of elements by slow neutrons, which produced heavier elements and isotopes.[6] Then, in December 1938, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann at Hahn’s laboratory in Berlin-Dahlem bombarded uranium with slowed neutrons,[7] and discovered that barium had been produced, and therefore that the uranium nucleus had been split.[6] Hahn wrote to his colleague Lise Meitner, who, with her nephew Otto Robert Frisch, developed a theoretical justification which they published in Nature in 1939.[8][9] This phenomenon was a new type of nuclear disintegration, and was more powerful than any seen before. Frisch and Meitner calculated that the energy released by each disintegration was approximately 200,000,000 electron volts. By analogy with the division of biological cells, they named the process ”fission”.[10]

Paris Group

This was followed up by a group of scientists at the Collège de France in Paris: Frédéric Joliot-Curie, Hans von Halban, Lew Kowarski, and Francis Perrin. In February 1939, the Paris Group showed that when fission occurs in uranium, two or three extra neutrons are given off. This important observation suggested that a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction might be possible.[11] The term ”atomic bomb” was already familiar to the British public through the writings of H. G. Wells, in his 1913 novel The World Set Free.[12] It was immediately apparent to many scientists that, in theory at least, an extremely powerful explosive could be created, although most still considered an atomic bomb was an impossibility.[13] Perrin defined a critical mass of uranium to be the smallest amount that could sustain a chain reaction.[14] The neutrons used to cause fission in uranium are considered slow neutrons, but when neutrons are released during a fission reaction they are released as fast neutrons which have much more speed and energy. Thus, in order to create a sustained chain reaction, there existed a need for a neutron moderator to contain and slow the fast neutrons until they reached a usable energy level.[15] The College de France found that both water and graphite could be used as acceptable moderators. [16] …